the Tomb of King Tut

Howard Carter's discovery of King Tutankhamun's tomb (KV 62) in 1922 remains one of the greatest and most renown archaeological finds ever made as a result of its unique, nearly intact state at the time of discovery and the resulting wealth of funerary objects recovered from it. Funded by his patron, Lord Carnarvon, Carter spent multiple years in search of the tomb before uncovering its entrance in the Valley of the Kings on Luxor's west bank (within the Necropolis of Ancient Thebes, now a World Heritage Site).

King Tutankhamun was an 18th dynasty Egyptian pharaoh thought to have come to power as a child around the age of nine and ruling for only a decade until his untimely death c. 1323 BC. His tomb is perhaps the most famous of Egypt’s pharaonic tombs and remains open to the public for visitation. In comparison to other pharaonic tombs, KV 62 is relatively small and simple, consisting of an entrance corridor and just four chambers carved into the Valley floor. Only the burial chamber walls were fully plastered and painted. However, the unusual style and iconography of the paintings are significant in comparison to other KV tombs.

In 2009, the Getty Conservation Institute began a multi-year collaborative project with Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) for the conservation and management of KV 62. The project, directed by Dr. Neville Agnew and led by Lorinda Wong, focused on examining the possible damaging effects of heavy visitor traffic on the tomb and wall paintings; evaluating concern that the "brown spots" or biodeterioration could be active and growing; and addressing deterioration issues such as flaking and loss of paint, previous treatments such as heavy surface coatings, and dust accumulation inside the tomb and on the wall paintings. Additionally, analysis and characterization of the original painting and plastering technology formed a large component of the project.

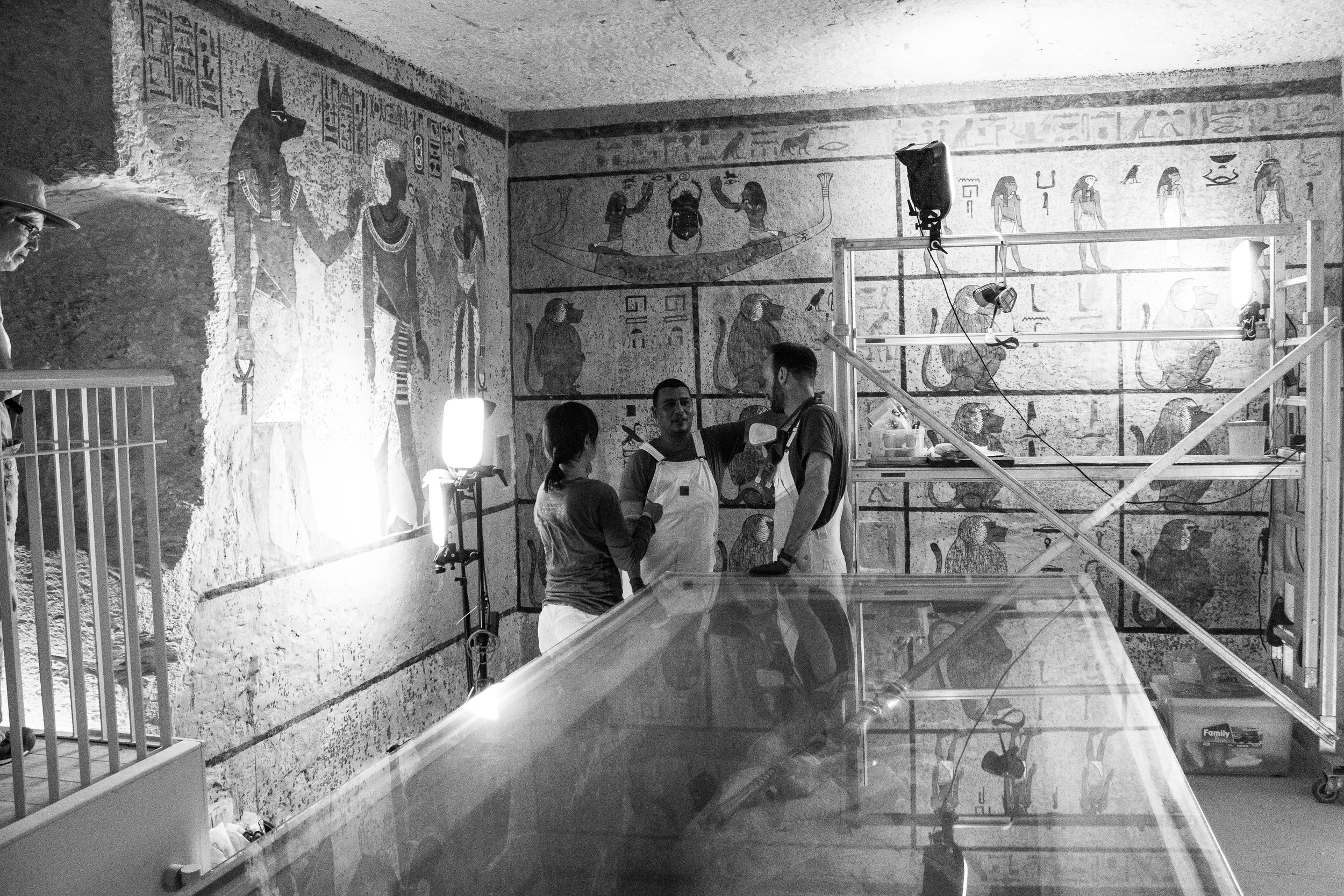

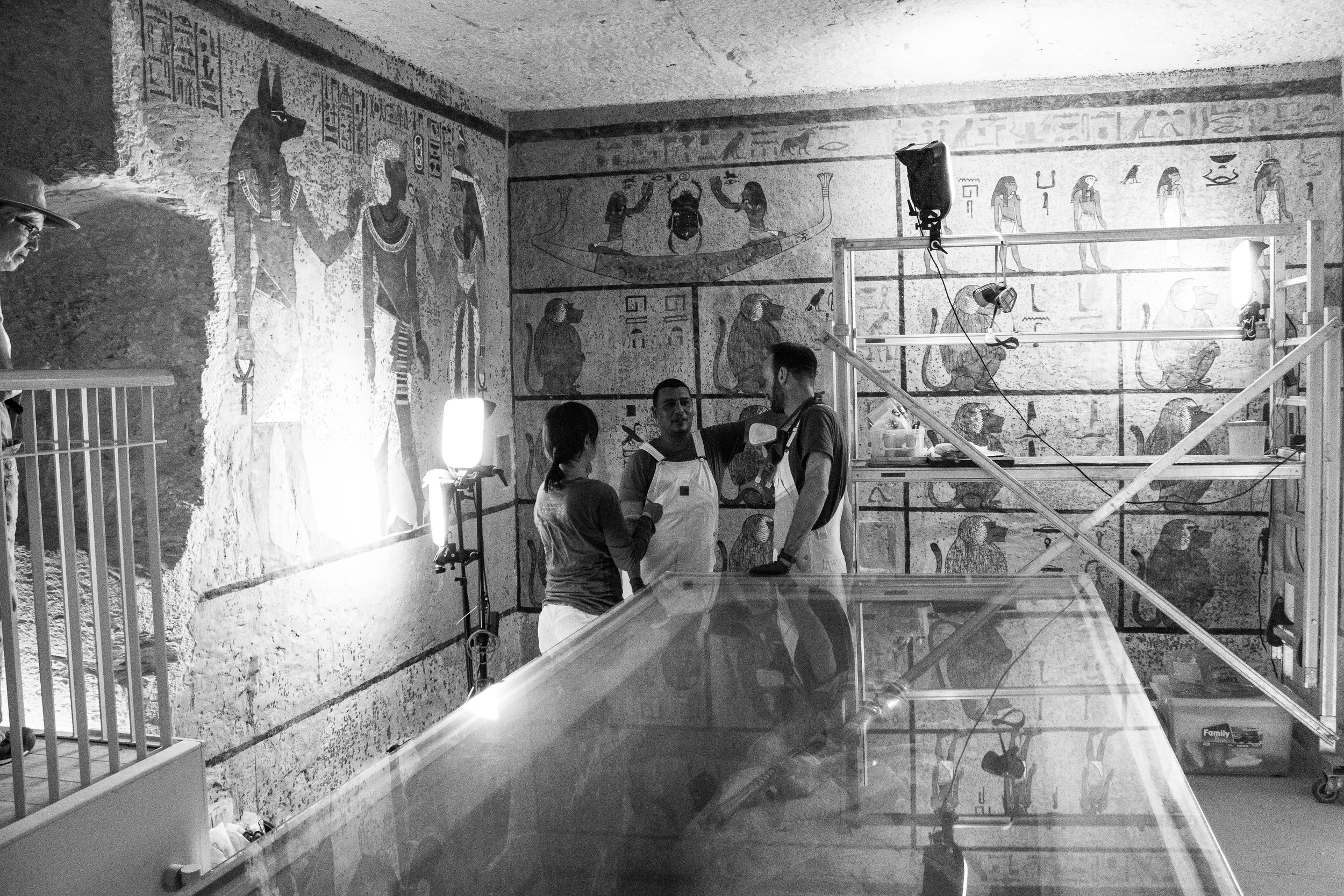

Part of the conservation team inside the painted burial chamber.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Hot air balloons landing in the desert south of the sacred mountain, El Qurn, where the Valleys of the Nobles, Queens and Kings are located.

Image © Katey Corda, 2017

Daybreak in the Valley of the Kings. The entrance to King Tut's tomb is located just to the right of the captured frame.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

The entrance to KV 62, showing a group of tourists reviewing signage with a member of the conservation team.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Inside the antechamber of the tomb showing the new visitor platform constructed as part of the project initiative and the painted burial chamber beyond. Conservation team leader, Lorinda Wong, is pictured giving a video interview.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Visitors to the tomb observing the burial chamber from the viewing platform.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

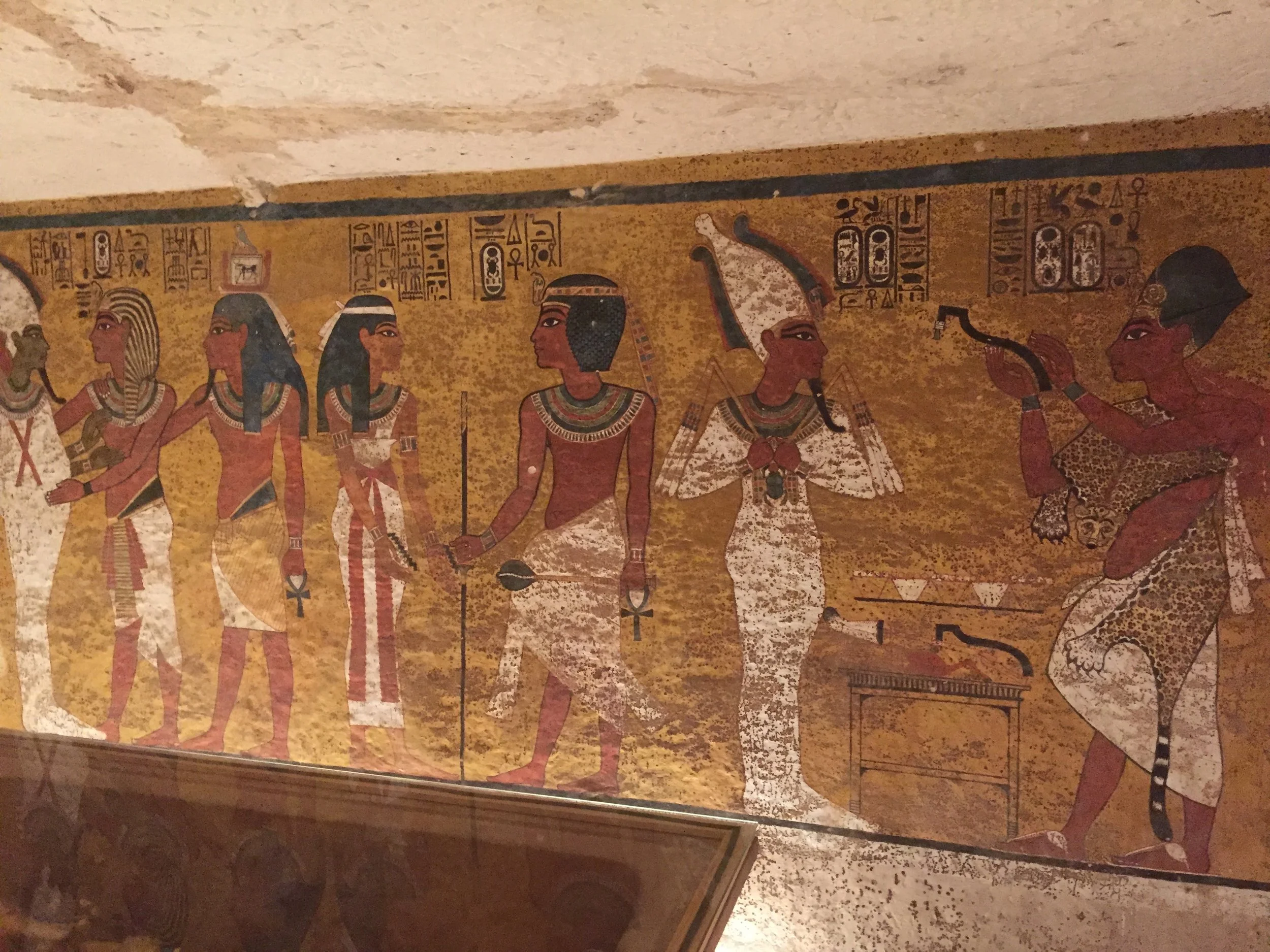

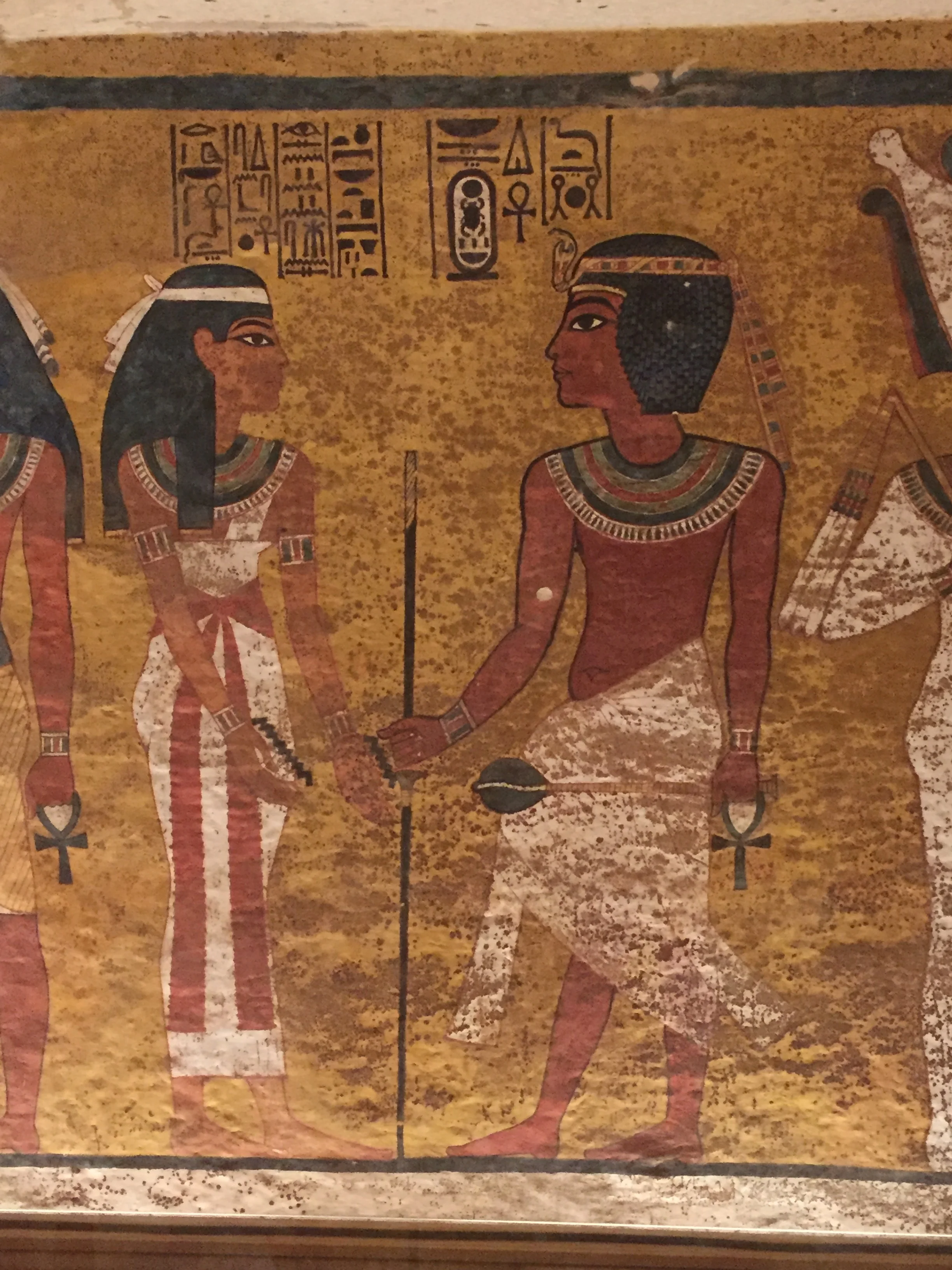

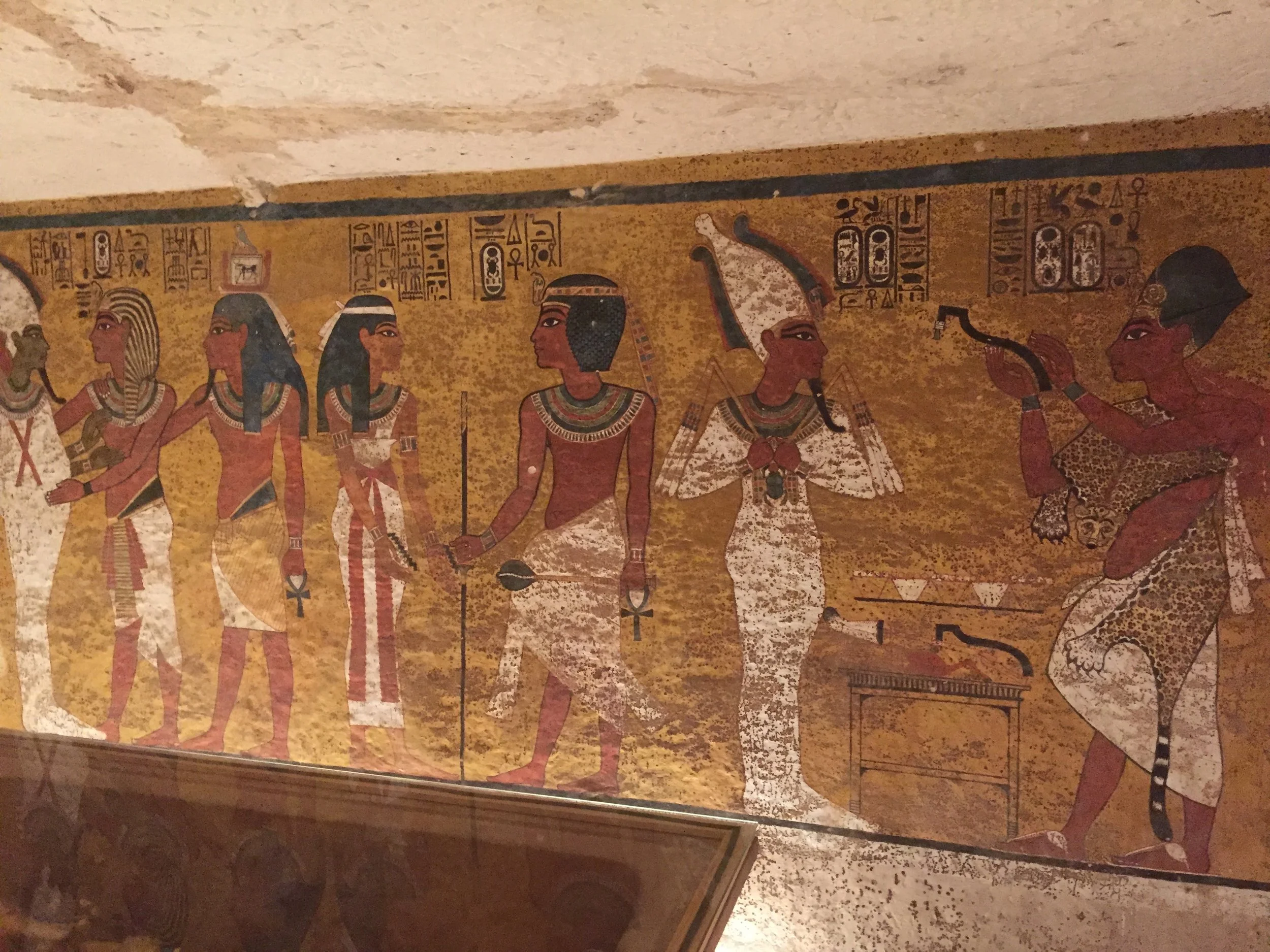

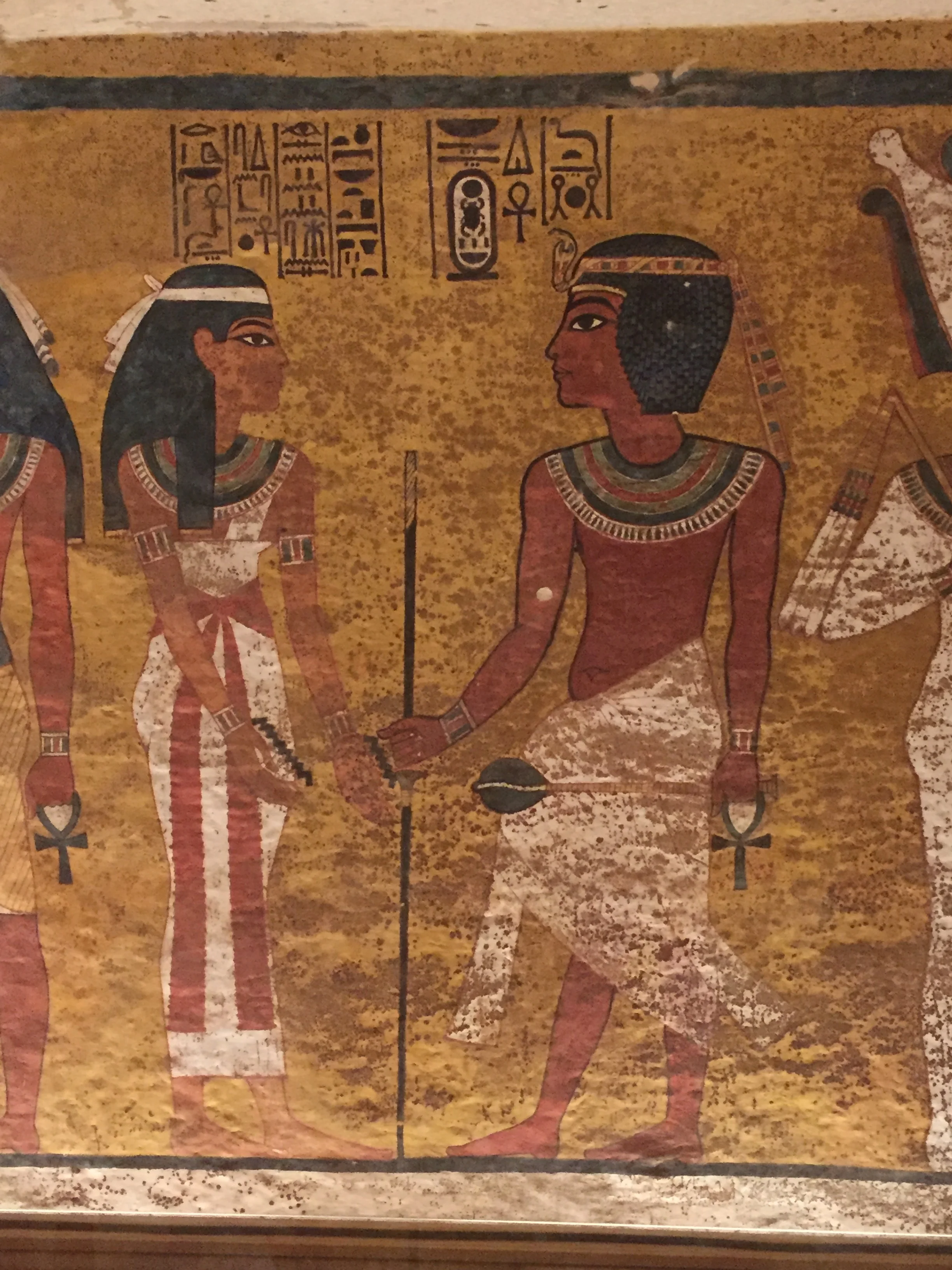

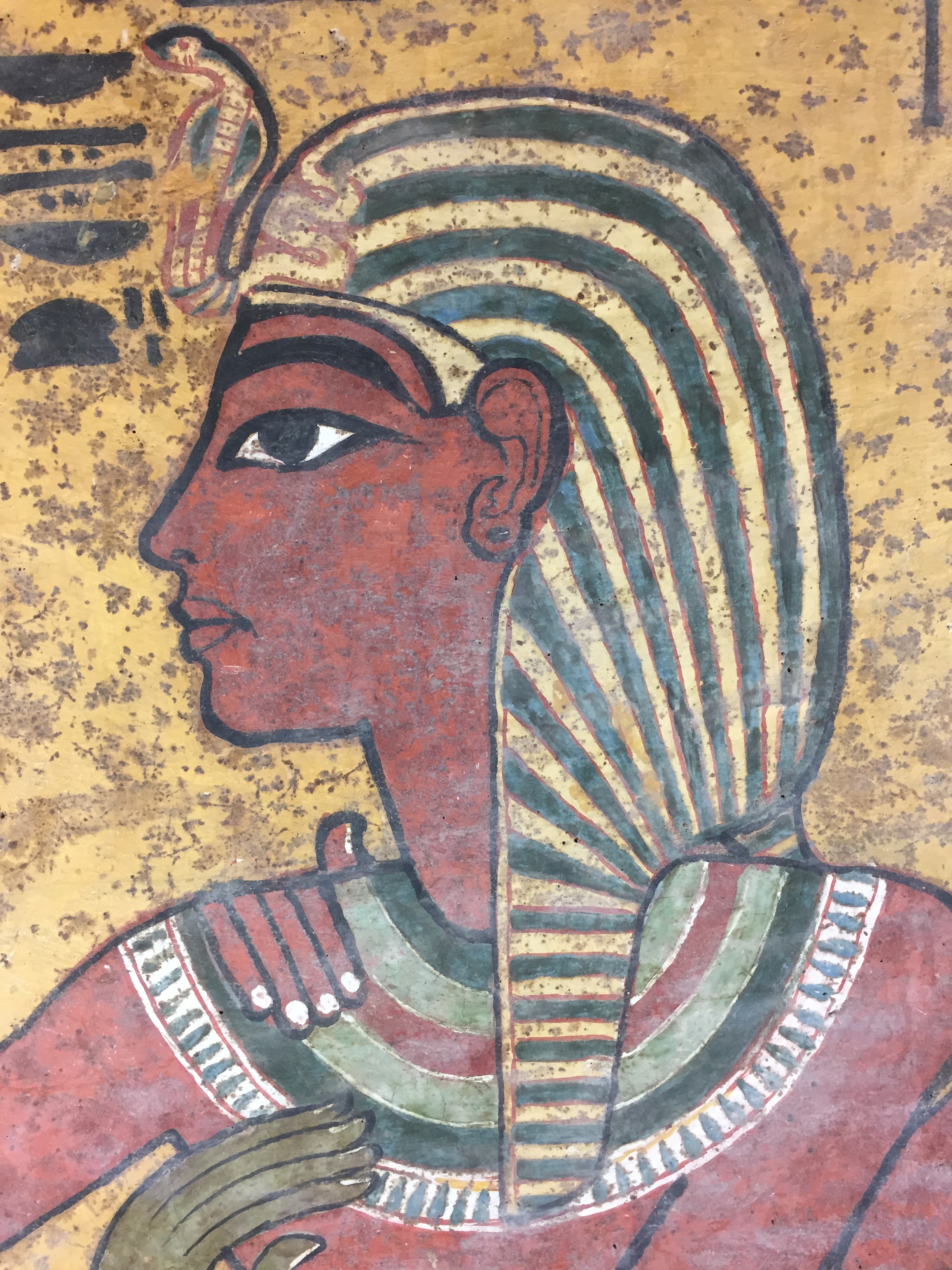

Iconography painted on the north wall of the burial chamber. Large figures in a style recalling the Amarna period are painted against a bright yellow background.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Tutankhamun, depicted in the form of a living king, being welcomed into the realm of the gods by the goddess Nut.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

The original, carved and painted stone sarcophagus sits in its original position in the center of the burial chamber. It houses Tut's original, carved and gilded outermost wooden coffin.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

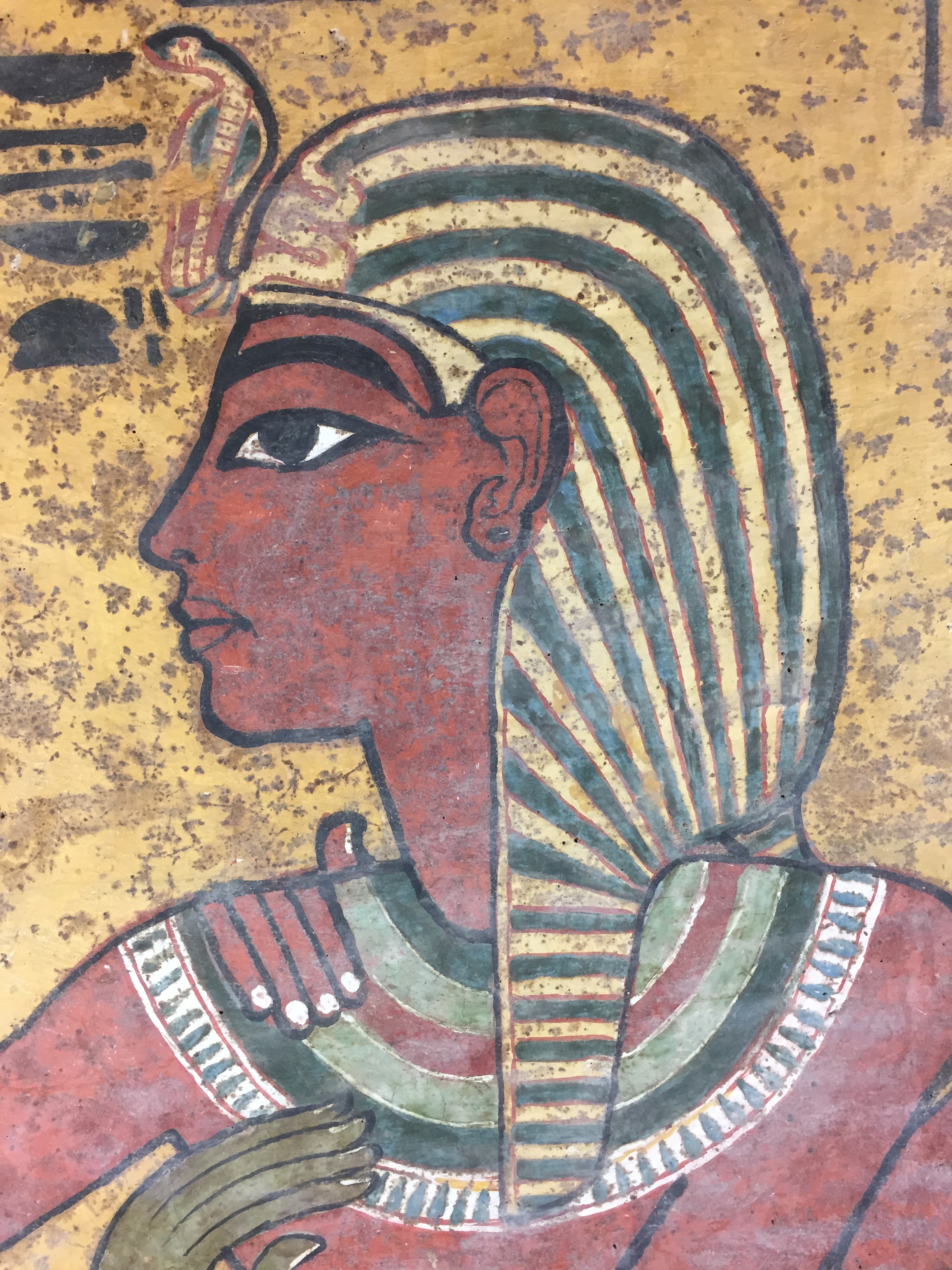

Painted depiction of King Tutankhamun.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

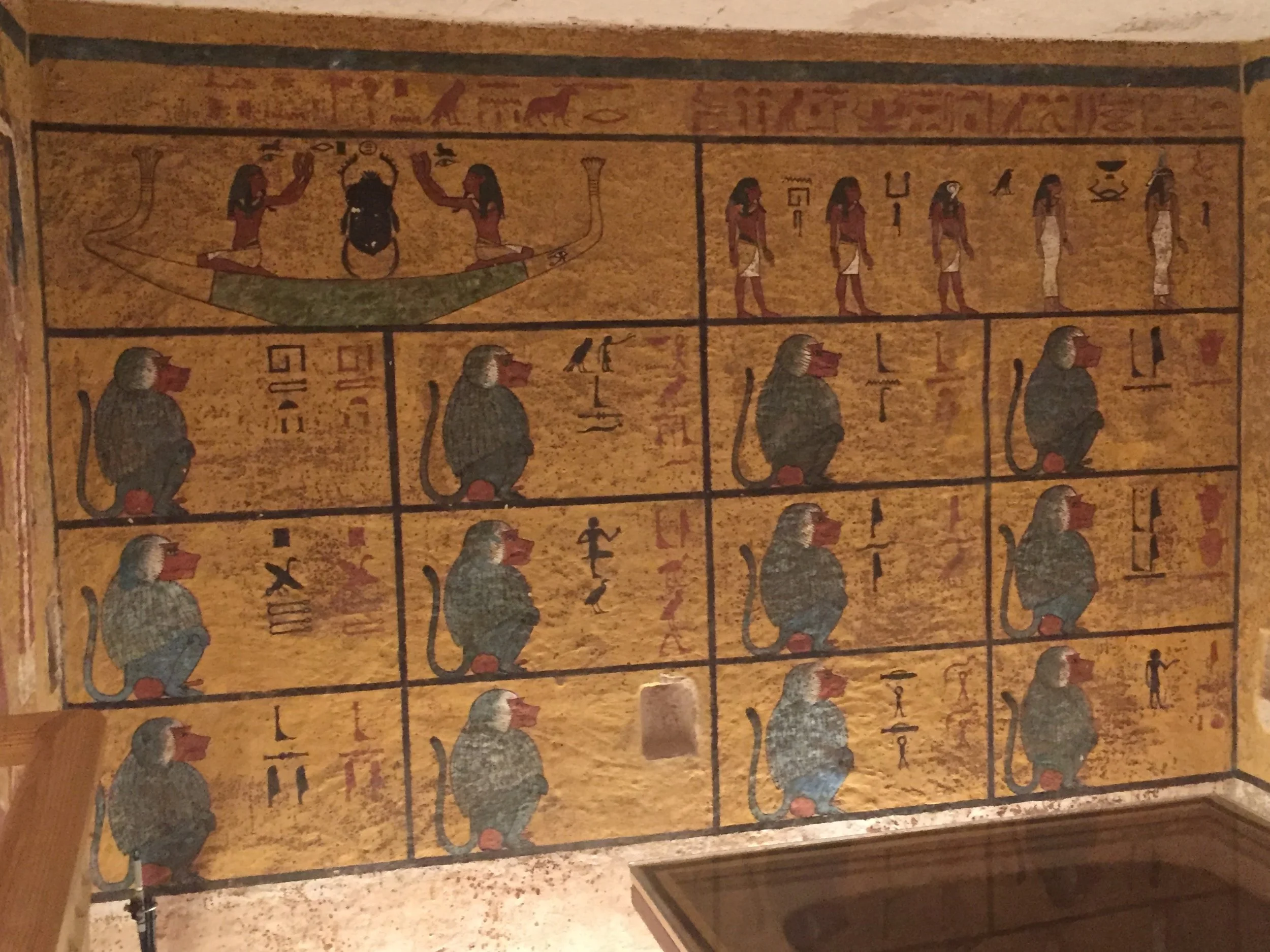

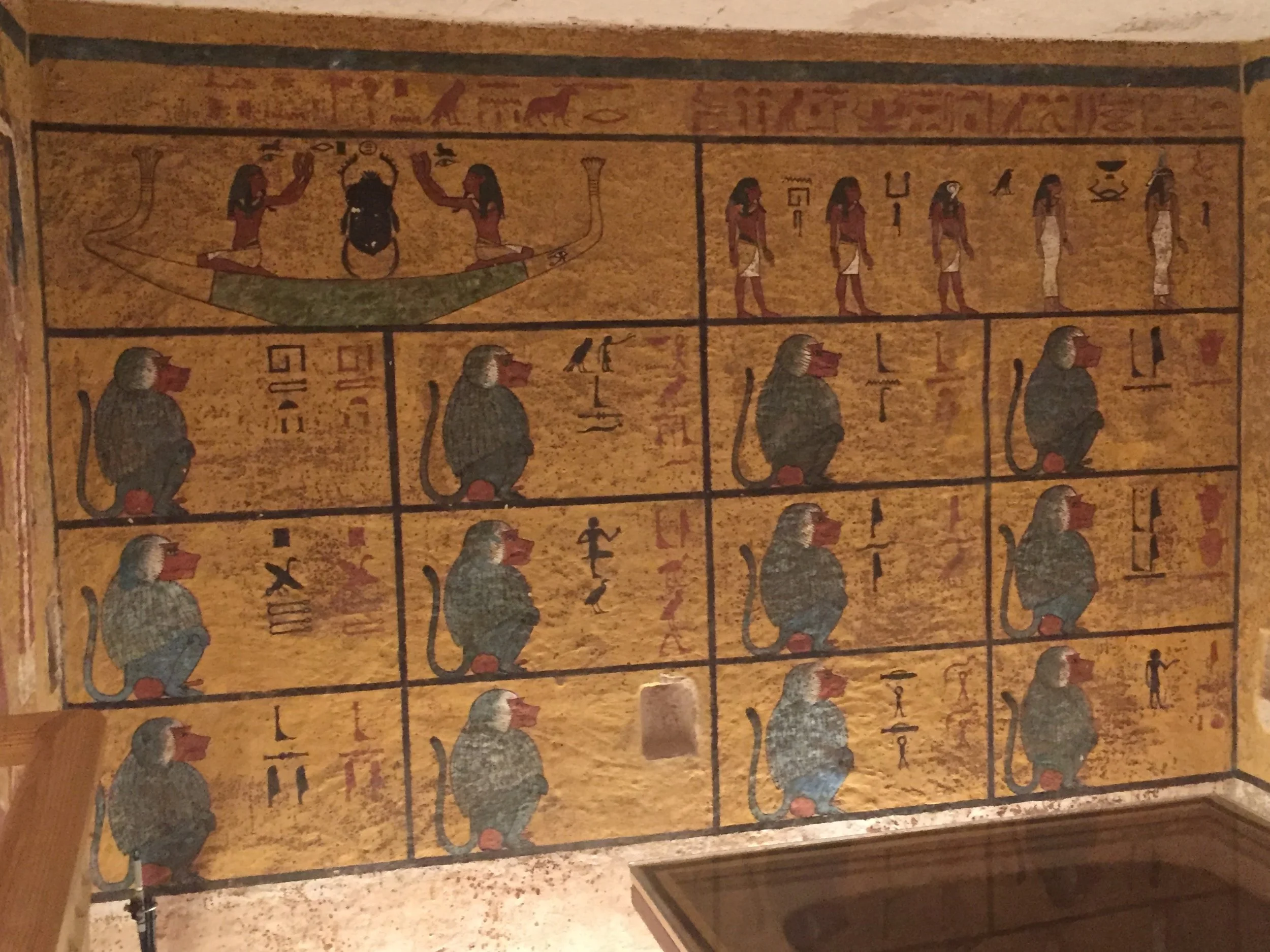

The west wall of the burial chamber depicts an extract from the Book of Amduat or “What is in the Underworld”, including twelve baboon-deities, representing the twelve hours of the night.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

The rock walls of the tomb were cut and carved with chisels and other hand tools. Unpainted areas of the wall surface were chiseled to a smoother finish while the rock in the burial chamber was left in a rougher state in preparation for plaster and painting. In some parts of this tomb, therefore, finely cut but undecorated walls were originally regarded as a finished treatment as much as those with painting.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

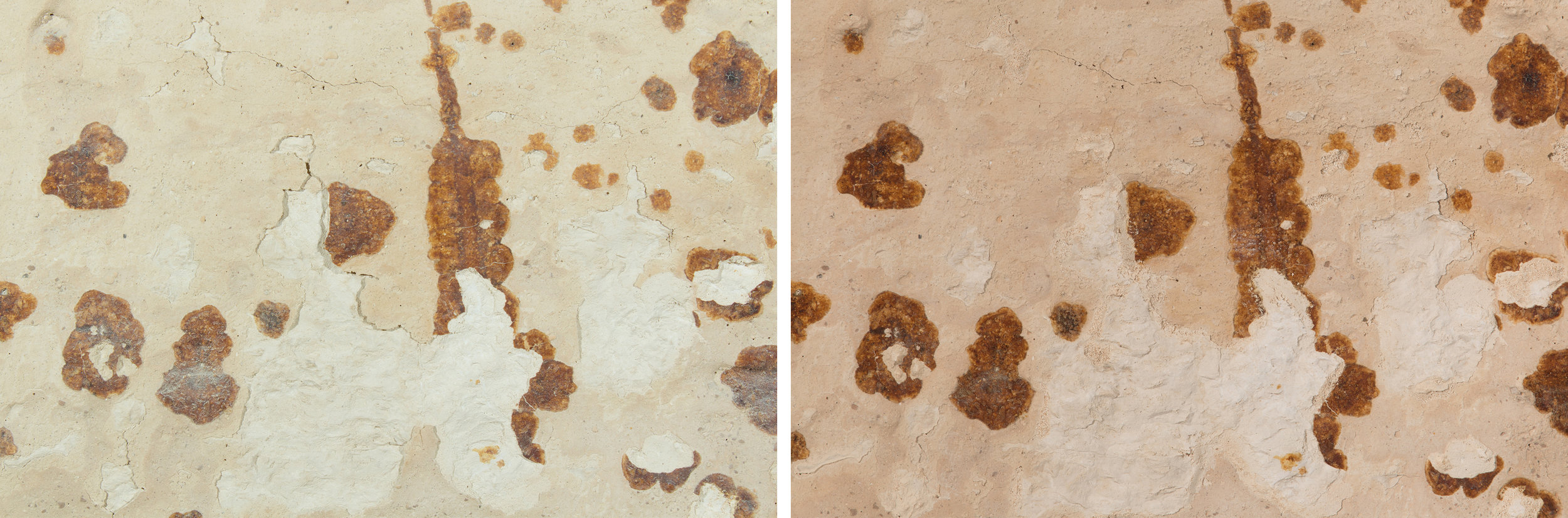

Plasters were applied to the rock-cut walls of Egyptian tombs to provide a suitable substrate for painting among other reasons. The rough finish of the plaster in Tut's tomb is unusual. Trowel and hand marks indicate that plasters were applied quickly and roughly.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

The team set up for conservation treatment of the wall paintings.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Environmental monitoring of conditions both inside and outside the tomb was established early in the project with data collected through the duration.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Environmental monitoring of conditions both inside and outside the tomb was established early in the project with data collected through the duration.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Preparing for removal of dust from the wall paintings.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Dust deposition has been a pervasive within the tomb. Fine dust settled on the painted surface in a thick layer, obscuring the imagery. Attempts to dust the paintings outside of the conservation project have led to loss in areas of paint layer instability.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Dust reduction was a two-step process. An air brush was first used in conjunction with a mechanical brush to carefully lift dust from the paint surface and prevent it from resettling in small cracks and fissures.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Dust reduction was a two-step process. An air brush was first used in conjunction with a mechanical brush to carefully lift dust from the paint surface and prevent it from resettling in small cracks and fissures.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

In a second step, a damp sponge was tamped over a thin layer of tissue to absorb remaining dust and lift it from the surface.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

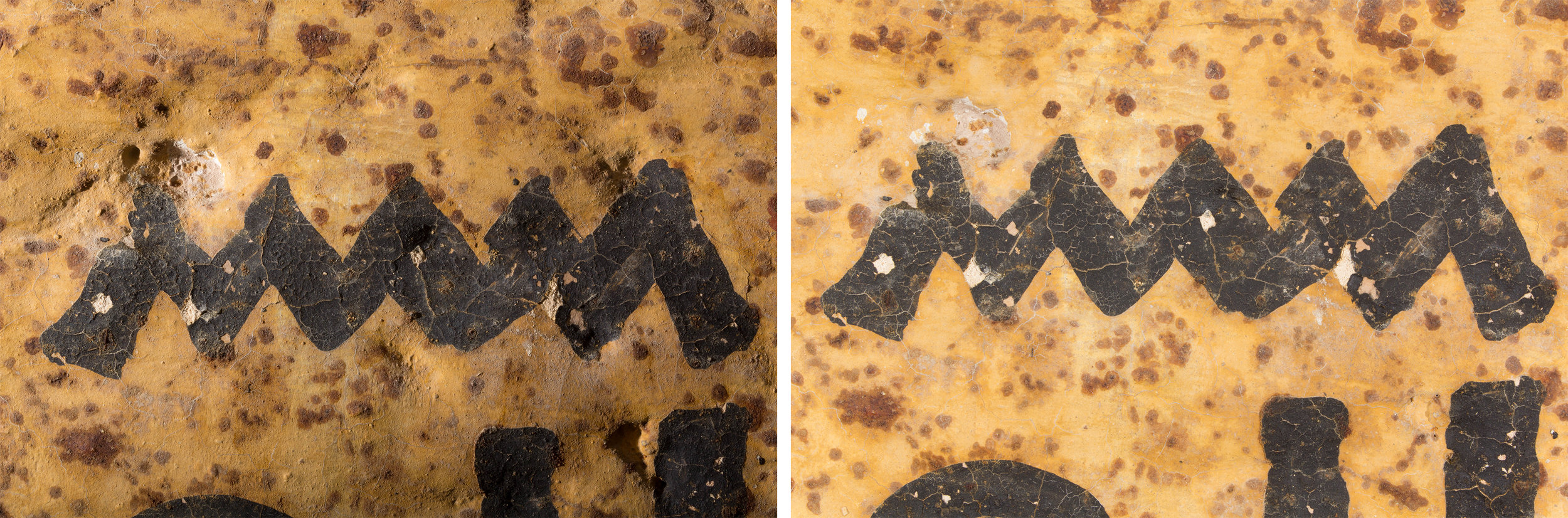

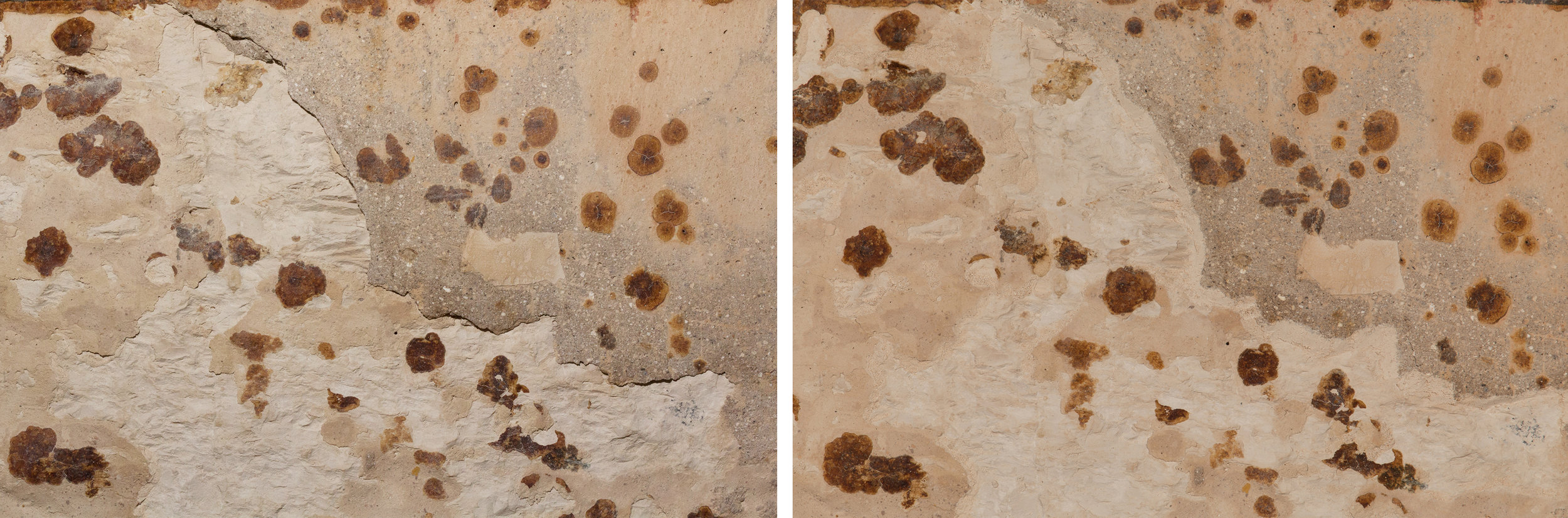

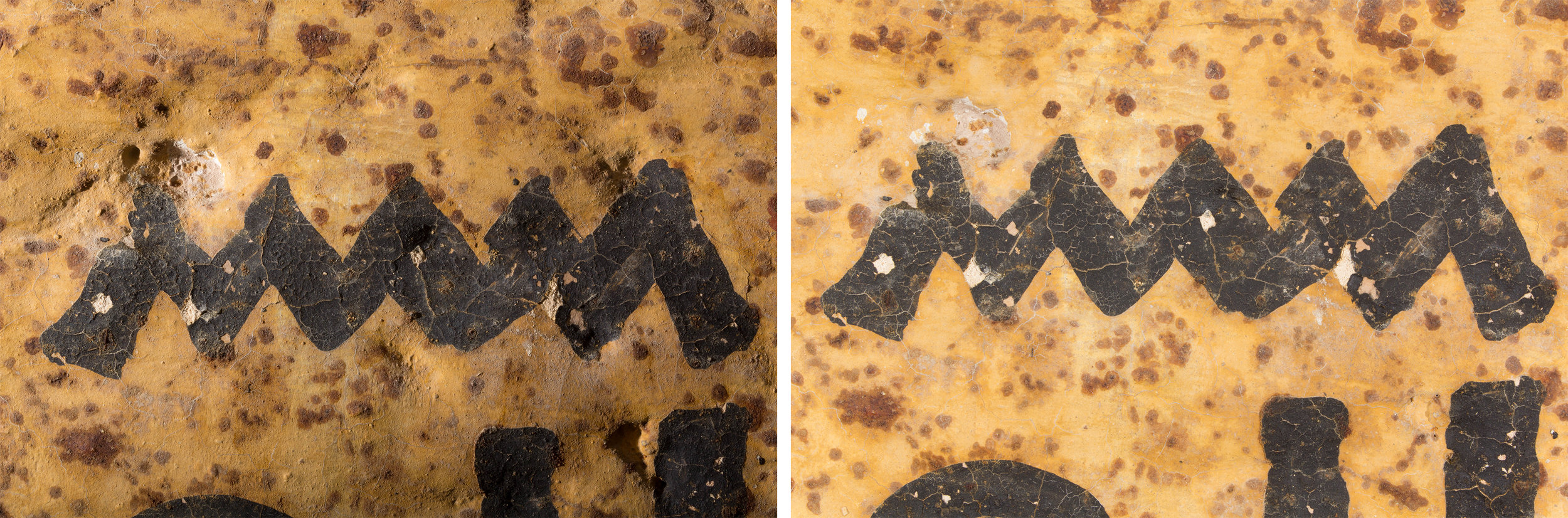

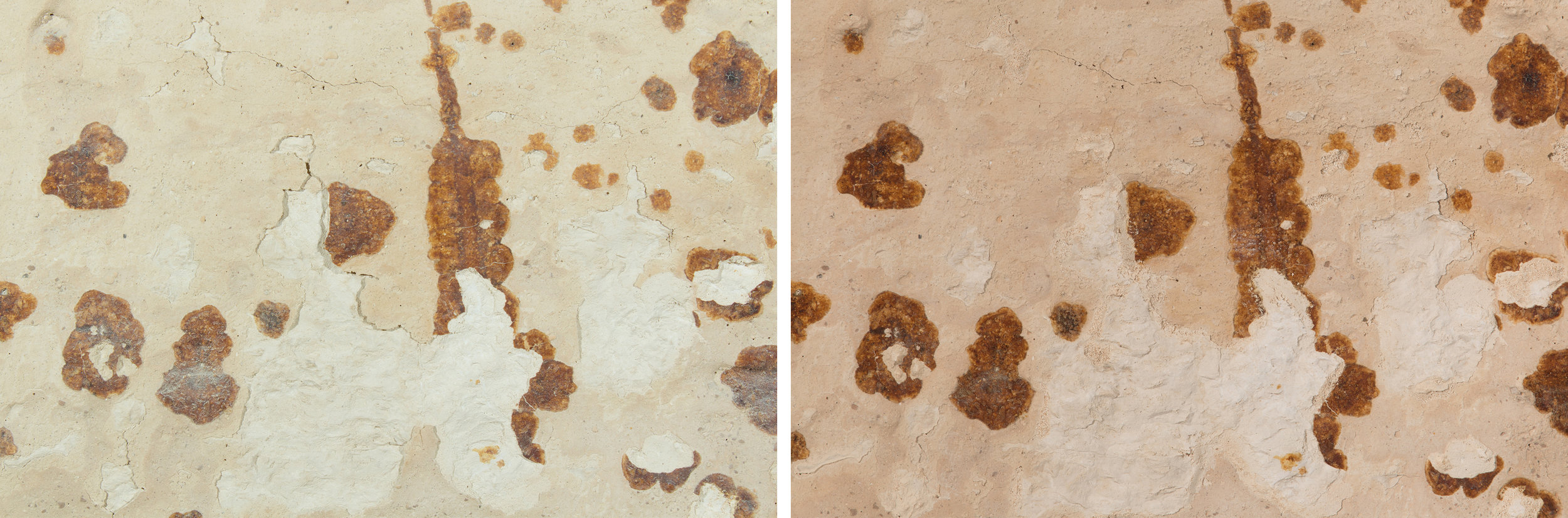

The wall painting before (left) and after (right) dust reduction.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

The wall painting before (left) and after (right) dust reduction.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

The wall painting before (left) and after (right) dust reduction, shown in raking light.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

The wall painting before (left) and after (right) dust reduction.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

A thick layer of dust was also removed from the carved and decorated stone sarcophagus.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Traces of the organic pigment, orpiment, were found on the stone sarcophagus.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Multiple layers of non-original coatings and drips from previous interventions covered the surface of the wall paintings prior to treatment. The coatings were extremely glossy in some areas while some drips had blanched.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Blanched, non-original surface coatings covering the surface of the wall paintings prior to treatment.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Non-original coatings and drips from previous interventions were reduced as far as possible by using an appropriate solvent to solublize and absorb them into tissue.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Non-original coatings and drips from previous interventions were reduced as far as possible by using an appropriate solvent to solublize and absorb them into tissue.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

A small square of glossy coating is shown remaining on the figure's arm following reduction from the surrounding area.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

The non-original coatings had begun to deteriorate and yellow, discoloring the paintings. A yellowing coating is visible where it remains on the left side of the image as compared to where it has been removed from the right.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

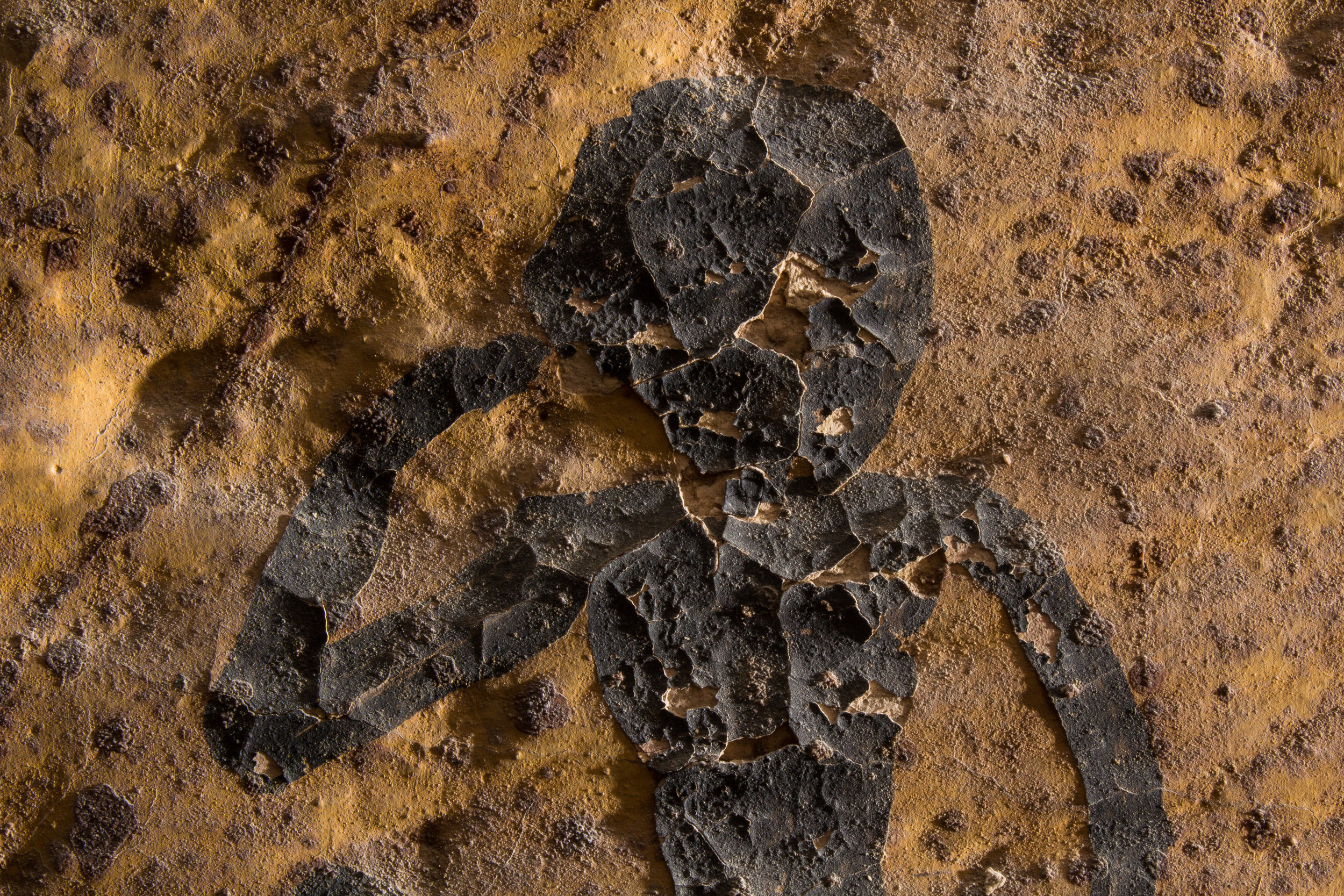

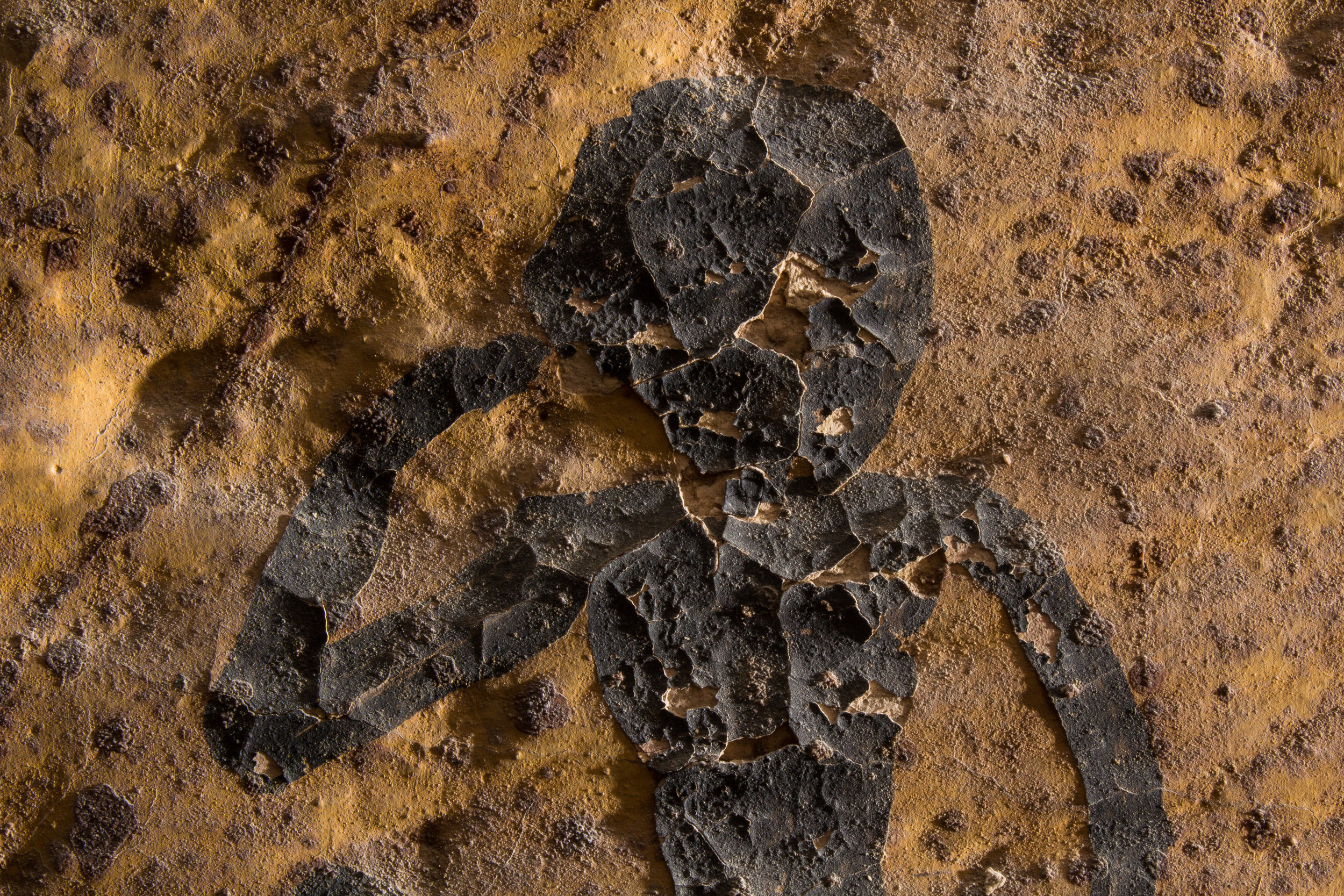

The stabilization of curling and flaking paint was a key component of the project, particularly on the east wall, as it was at great risk of loss from mechanical damage.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

A syringe and needle was used to apply an appropriate adhesive behind each flake, readhering them to the substrate.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

A syringe and needle was used to apply an appropriate adhesive behind each flake, readhering them to the substrate.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

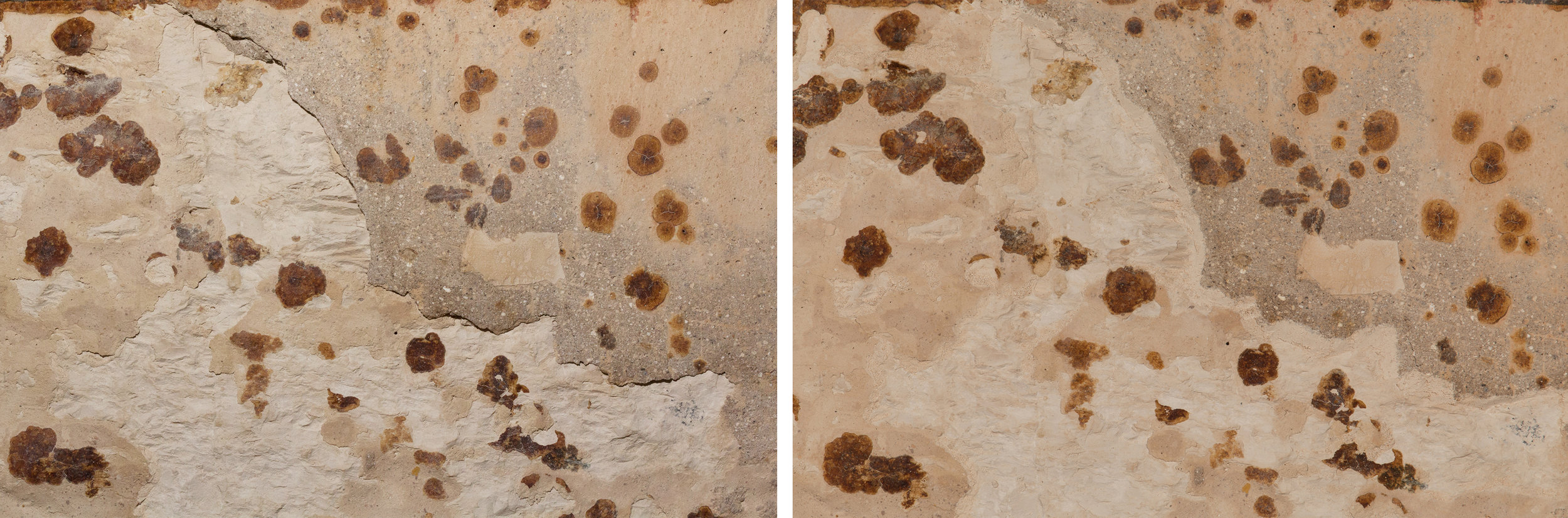

Area of flaking paint before (left) and after (right) readhesion, shown in raking light.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

Area of flaking paint before (left) and after (right) readhesion, shown in raking light.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

To stabilize larger, thicker flakes of paint and plaster, a custom bulking adhesive was applied by pipette behind and around the edges of each flake.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

To stabilize larger, thicker flakes of paint and plaster, a custom bulking adhesive was applied by pipette behind and around the edges of each flake.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016

An area of thick flaking is pictured before (left) and after (right) stabilization with a custom bulking adhesive.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

An area of thick flaking is pictured before (left) and after (right) stabilization with a custom bulking adhesive.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

For areas where the bulking adhesive was insufficient - for example, to stabilize patches of original plaster - a repair material was applied around the edges to readhere it to the substrate.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

For areas where the bulking adhesive was insufficient - for example, to stabilize patches of original plaster - a repair material was applied around the edges to readhere it to the substrate.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Area of original plaster, stabilized with an edge repair.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Area of original plaster shown before (left) and after (right) stabilization with an edge repair.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

The unpainted rock-cut walls in the antechamber and entrance corridor had become extremely dirty over the years as a result of tourists touching them, leaving a greasy, black surface appearance. The dirt was reduced with poultices.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Greasy, black hand-marks in the entrance corridor shown before (left) and after (right) poultice reduction.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

A small square of greasy dirt deposited by tourist's handprints, is shown remaining on the rock-cut surface of the antechamber following its reduction from the surrounding areas.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Members of the 2017 conservation team.

Image © J. Paul Getty Trust, 2017

Sugar cane fields in the agricultural lands that extend across Luxor's west bank.

Image © Katey Corda, 2016

Village life on Luxor's west bank.

Image © Katey Corda, 2017