The Sheesh Mahal

The Ahhichattragarh Fort and Palace Complex at Nagaur in Rajasthan, India is renown for its exquisite complex of painted palaces and gardens. Most of the palaces now visible were built under the patronage of Bakht Singh, who ruled Nagaur from 1725 to 1751. The wall paintings are among the finest examples of 18th century Rajput-Mughal paintings in Rajasthan.

The fort complex has been the subject of major conservation initiatives since the 1990s under the direction of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust (MMT) and His Highness Maharaja Gaj Singh II. In 2005, the Courtauld Institute of Art, funded by the Helen Hamlyn Trust and later, the Getty Conservation Institute, was commissioned to undertake a survey of the fourteen surviving wall painting schemes and begin conservation investigations. The conservation team, led by Stephanie Bogan, Charlotte Martin de Fonjaudran and Sibylla Tringham, prioritized the Sheesh Mahal (or ‘Palace of Mirrors’) as the initial focus for conservation efforts.

The Sheesh Mahal features beautifully polished "araish" plaster work and paintings on both the internal and external walls. The decorative features reflect a celebration of the female world and the function of the palace used particularly during the rainy season. In the vault, women are represented sharing drinks and playing musical instruments amidst swirling monsoon clouds. The walls contain elaborate niches with paintings of dancing women and vases, while the dado level displays the beautiful inlaid mirror work.

The paintings were found to be at high risk of loss as a result of both extreme salt efflorescence and severe plaster detachment. Additionally, they were badly obscured and discolored by dirt and non-original coatings. Conservation treatment of the Sheesh Mahal was completed in 2013 but initiatives continue throughout the complex today with the support of the Leon Levy Foundation.

General view of the view of the Ahhichattragarh Fort and Palace Complex at Nagaur in Rajasthan, India.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

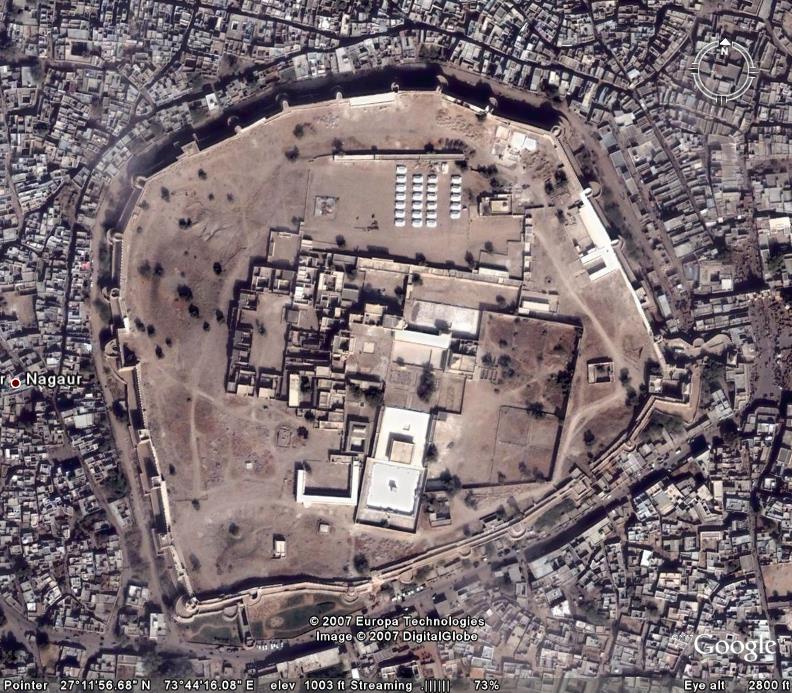

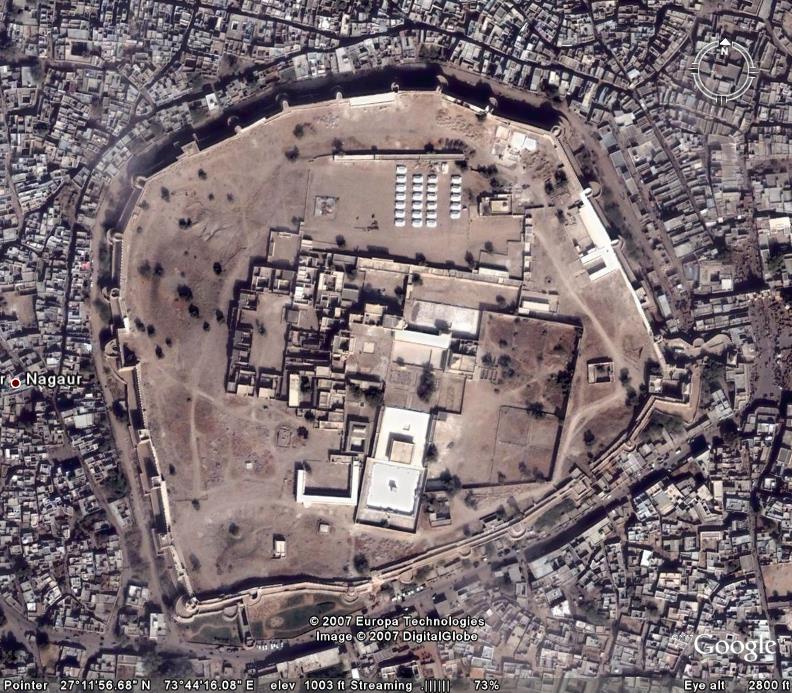

Satellite view of the Ahhichattragarh Fort and Palace Complex surrounded by the city of Nagaur in Rajasthan, India.

Image © Digitalglobe

Elevated view of an arcaded walkway, behind which lies the Sheesh Mahal and surrounding gardens.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Arcaded walkway though which lies the Sheesh Mahal building and garden.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

The beautiful Ahhichattragarh Fort and Palace Complex at night.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Exterior view of the Sheesh Mahal or "Palace of Mirrors". The building comprises a single vaulted hall with encircling veranda and garden courtyard.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Interior view of the Sheesh Mahal facing east, before conservation.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Interior view of the Sheesh Mahal facing west, before conservation.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

The plastered and painted exterior walls of the Sheesh Mahal.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Both interior and exterior palace surfaces are covered in "araish" plaster. It is historically composed of three layers, the uppermost of which is bright white in color and highly polished. Both technique and materials are remarkably similar to those employed by local masons today.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Once completely dry, the araish was decorated with paintings. In the vault, women are represented sharing drinks and playing musical instruments amidst swirling clouds during monsoon.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

In the vault, women are represented sharing drinks and playing musical instruments amidst swirling clouds during monsoon.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

In the vault, women are represented sharing drinks and playing musical instruments amidst swirling clouds during monsoon.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Detail of the painting in the vault in visible (left) and ultraviolet (right) light. Ultraviolet fluorescence exposes the faded organic materials originally used to depict the clouds and rain of the monsoon.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Environmental monitoring indicated that fluctuations in the internal microclimate were promoting the efflorescence of salts and causing deterioration of the painting.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Environmental monitoring indicated that fluctuations in the internal microclimate were promoting the efflorescence of salts and causing deterioration of the painting.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Salt crystals were pushing layers of paint off the wall.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Salt crystals were pushing layers of paint off the wall.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Salt efflorescences were removed by gentle brushing where possible. Poultices were then used to extract salt ions from within the plaster.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Before (left) and after (right) removal of salts from the wall paintings.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

An extremely glossy and discoloring non-original coating was removed from the surface of the painting with poultices.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Detail of the vault during coating removal. The coating is clearly visible in the upper portion of the image, giving the paintings a glossy and discolored appearance. Where it has been removed in the bottom portion of the image, the originally matte appearance of the surface is visible.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Example of the inlaid mirror work from which the palace derives its name. The image shows the araish during cleaning. A thick brownish-yellow dirt layer has been removed from the left side of the plaster but remains on the right side.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Tthe mirrored surfaces were similarly cleaned and polished.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Some of the mirrored work had been covered over by non-original repair material during a previous intervention. This was removed to expose the mirror beneath. The image shows a concealed area before (left) and after (right) cleaning.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Detail of the mirrored dado level before (left) and after (right) cleaning.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Detail of the mirrored dado level before (left) and after (right) cleaning.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

A thick brownish-yellow dirt layer was also removed from the upper walls. A multi-step process was used to protect the water-sensitive pigments during cleaning of the araish.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Paint layers were first covered with a naturally subliming material as protection during cleaning of the surrounding plaster.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

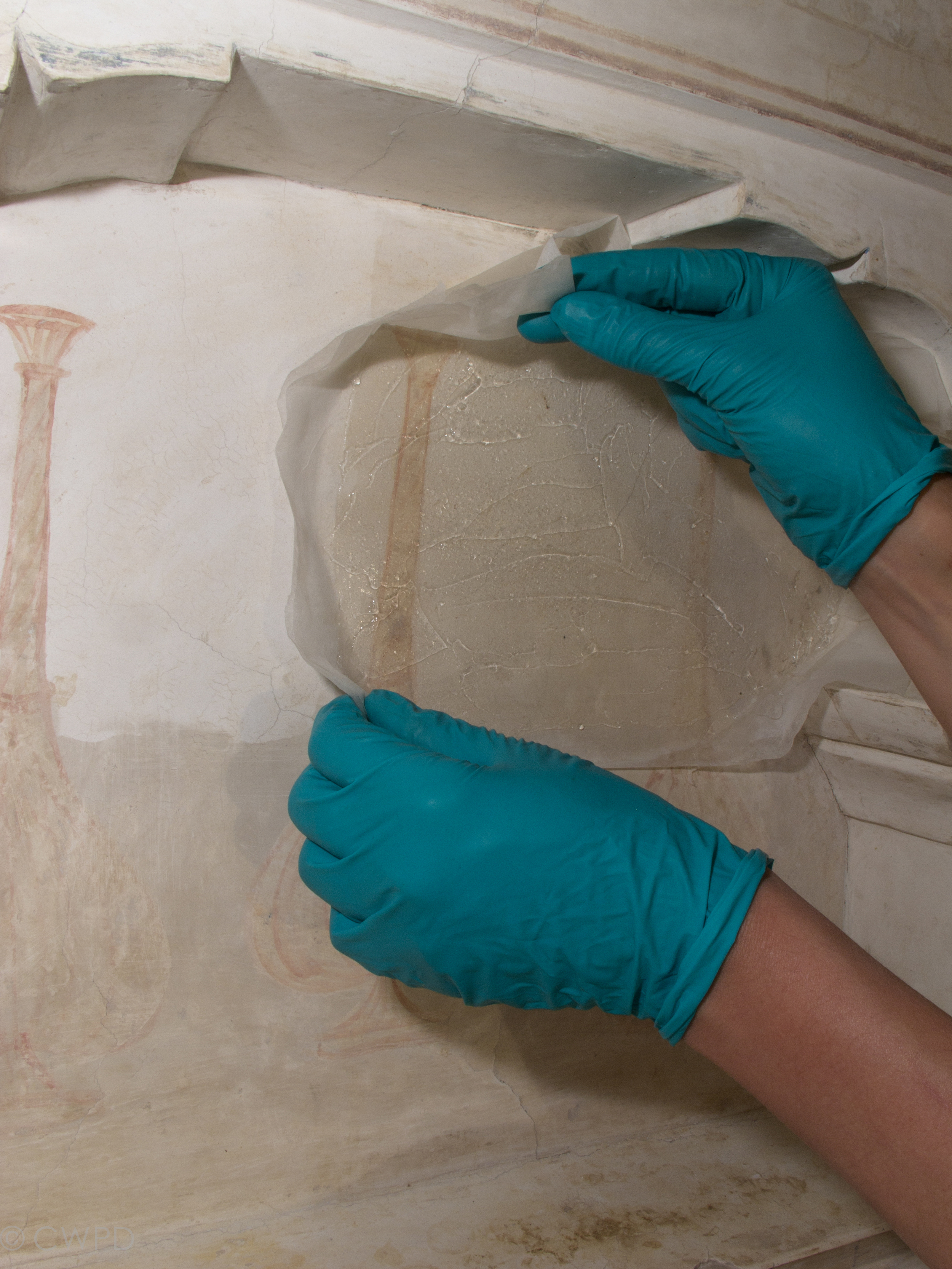

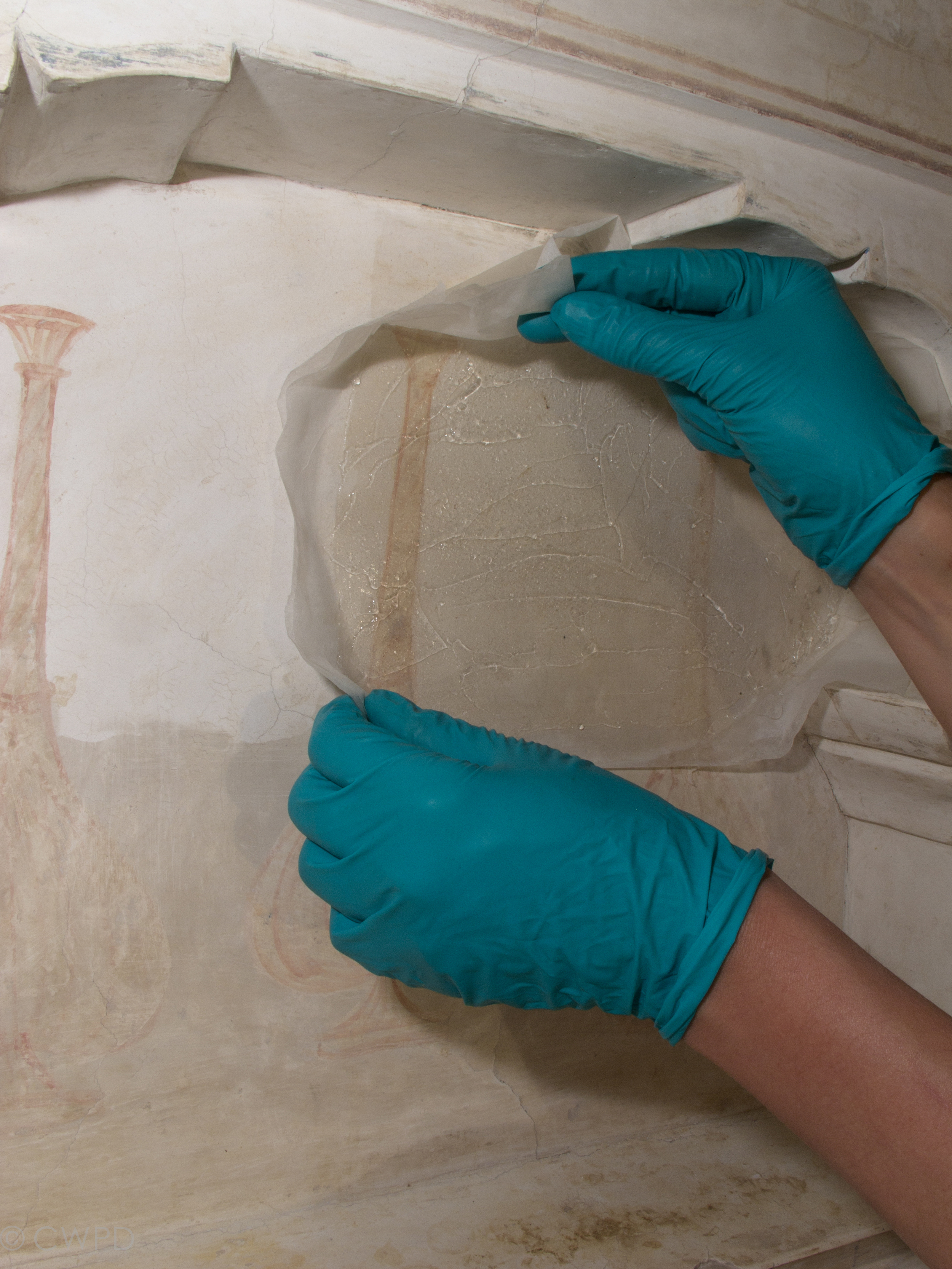

An intervention layer of tissue paper was then applied to the area.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

A gel-based system was applied over the tissue layer until the dirt layer beneath began to swell.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

The tissue was then peeled off, removing the gel poultice with it.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Sponges were used to clear the loosened dirt layer from the surface of the wall, leaving the painted surfaces unaffected.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Sponges were used to clear the loosened dirt layer from the surface of the wall, leaving the painted surfaces unaffected.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Example of a painted niche partially cleaned.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Example of a painted niche before (left) and after (right) cleaning.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Multiple small and large areas of detached and displaced plaster were readhered to the wall support through injection grouting. A custom grout compatible with the original materials was developed for the purpose.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Cotton wool was used to block holes where the grout could potentially leak out prior to setting.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Pipettes, syringes, needles and catheters were used as required to inject the custom grout, stabilizing areas of detached plaster.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Pipettes, syringes, needles and catheters were used as required to inject the custom grout, stabilizing areas of detached plaster.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Detail of the south wall before (left) and after (right) completion of conservation treatment.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

General view of the west wall before (left) and after (right) completion of conservation treatment.

Image © Courtauld CWPD

Detail of the west wall after conservation treatment.

Image © Courtauld CWPD