Deir el shelwit temple

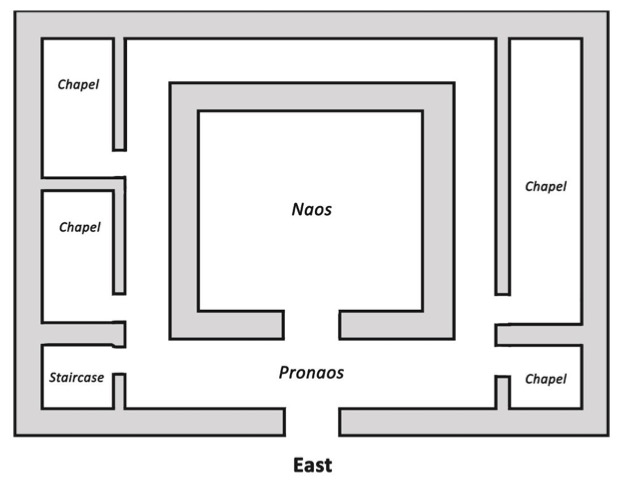

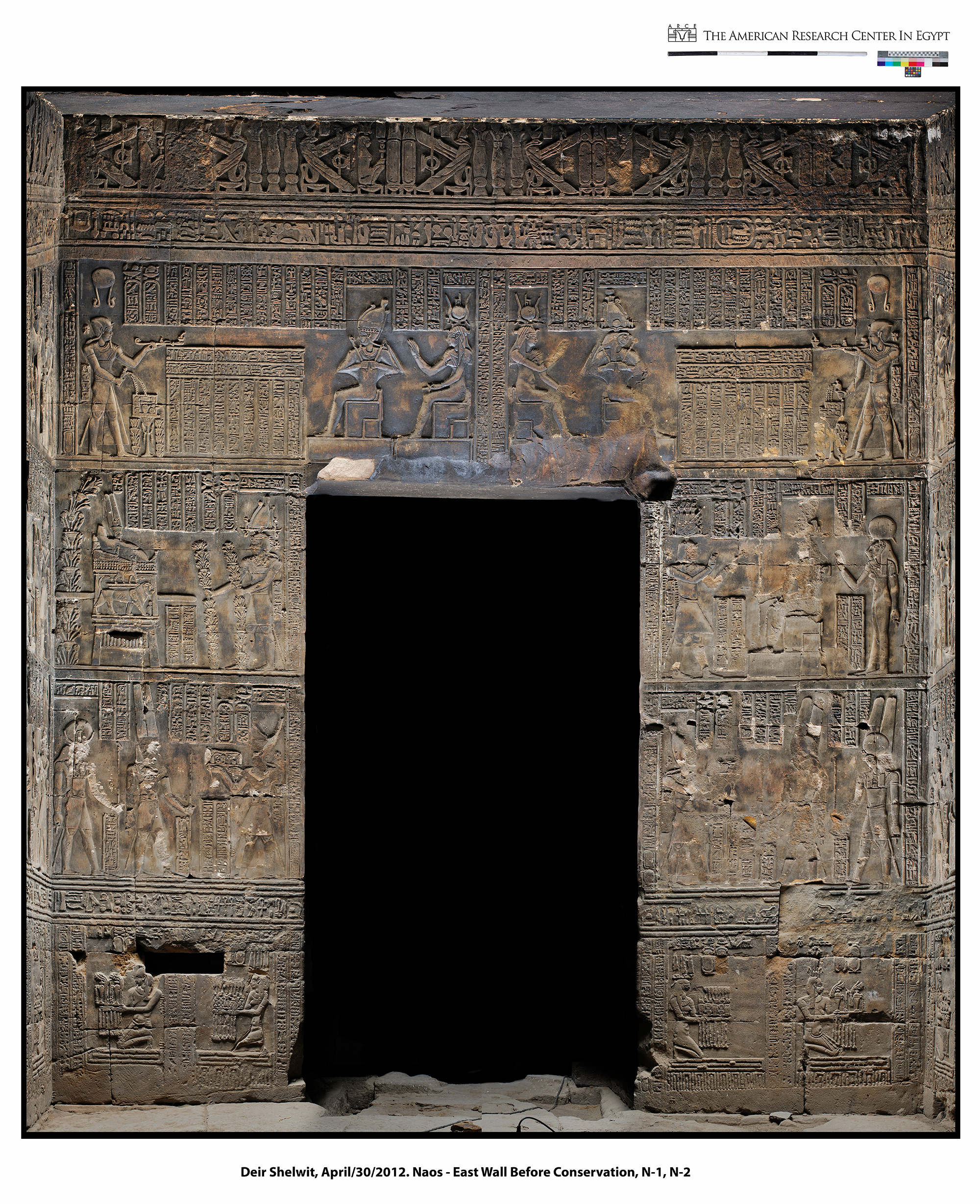

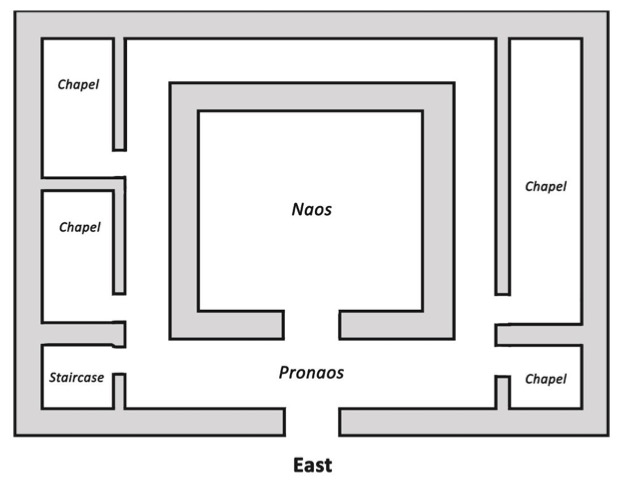

Deir el Shelwit is a Roman-era (1st-2nd century C.E.) sandstone temple located on Luxor’s West Bank. It is a small temple, composed of a central chamber, or naos, with surrounding corridor, four side chapels and a roof terrace. The façade and interior walls of the naos are decorated with intricately painted high-relief with inscriptions and scenes of Roman emperors making offerings to Egyptian gods. The project to conserve Deir el Shelwit was initiated in 2012 as a collaboration between the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) and the Supreme Council of Antiquities, with the aim of opening it to public visitation.

The initial phase was led by Katey Corda and Jennifer Porter and focused on preventive conservation measures necessary prior to remedial work. Measures included roof repairs to prevent water infiltration and the exclusion of a large colony of resident bats. Bats have the potential to severely damage both the historic fabric and the decorative surfaces of a building. Additionally, their guano can carry or host a variety of fungal and bacterial growths that are harmful to human health. A significant amount of time was dedicated to developing a compassionate and permanent removal strategy and its account was published upon completion of the 2012 campaign. Additional project components included background research, preliminary documentation, site set-up, and treatment trials for the cleaning of the wall paintings.

The temple of Deir el Shelwit sits at the interface of the desert and cultivated agricultural lands, 5 kilometers south of better-known sites such as the Valleys of the Kings and Queens.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Deir el Shelwit temple exterior.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Temple floorplan (diagram is not to scale).

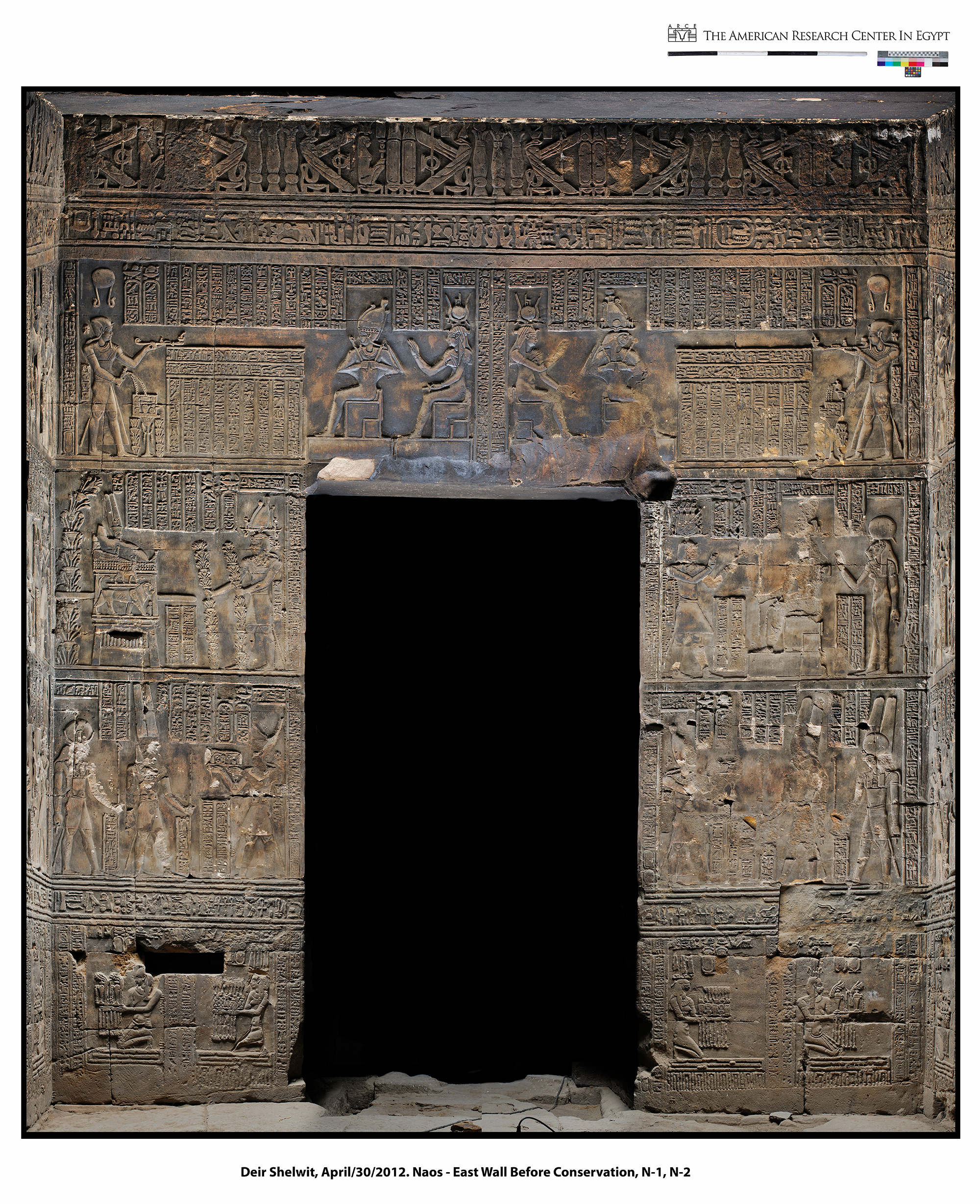

Reliefs on the east interior wall of the naos.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Inspection of the painted relief.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Inspection of the painted relief.

Image © ARCE, 2012

The interior walls of the temple are carved in high-relief and intricately painted.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of vibrant pigment remains on the interior walls.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Jennifer Porter and Katey Corda assessing the interior of the temple.

Image © ARCE, 2012

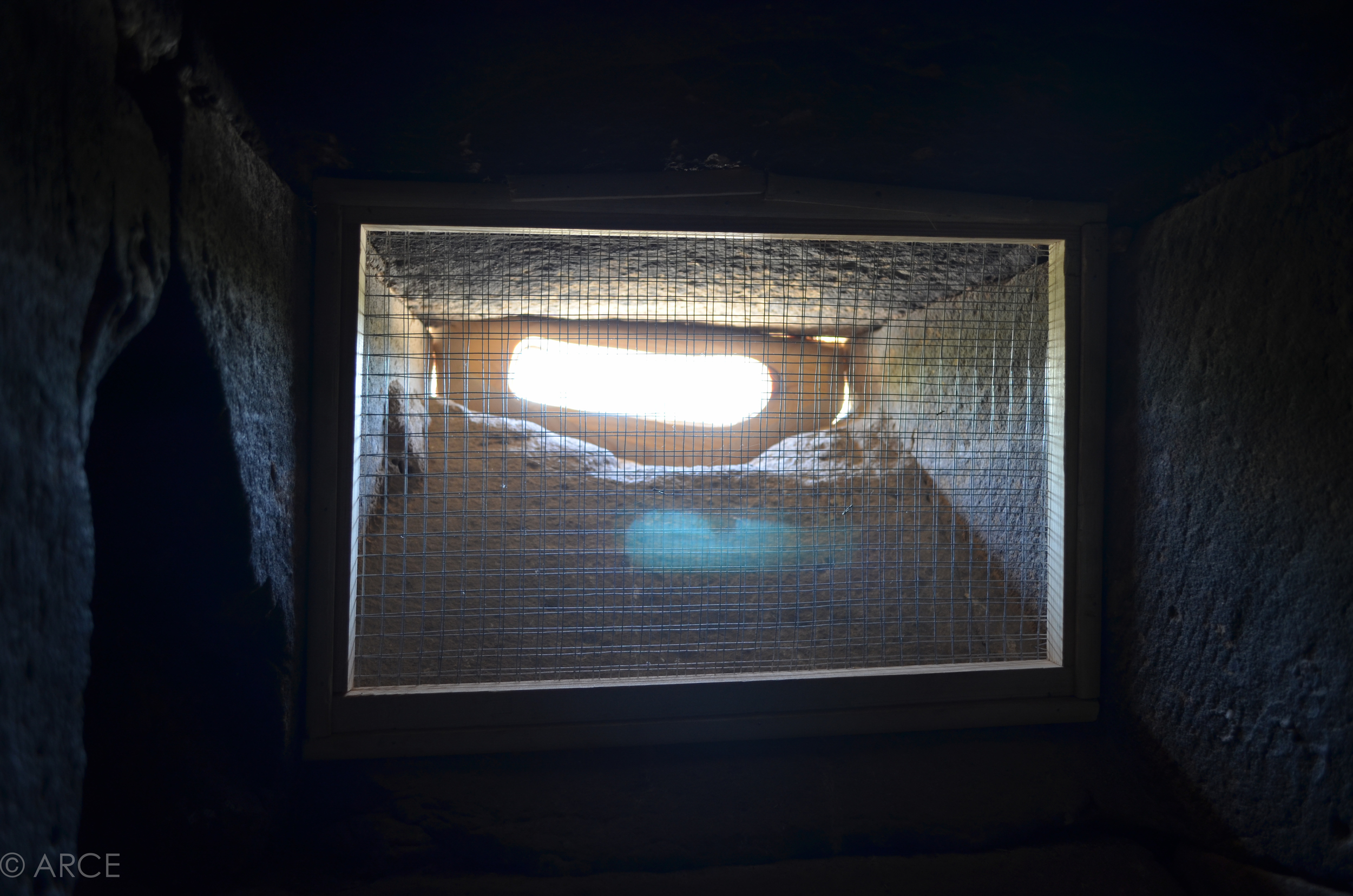

A bat colony was habituating in the side chapels, corridor and stairwell of the temple. Bats are a cause of mechanical damage to original surfaces, while their excrement causes staining and chemical deterioration of stone and paint layers and can host fungus and bacteria harmful to humans.

Image © ARCE, 2012

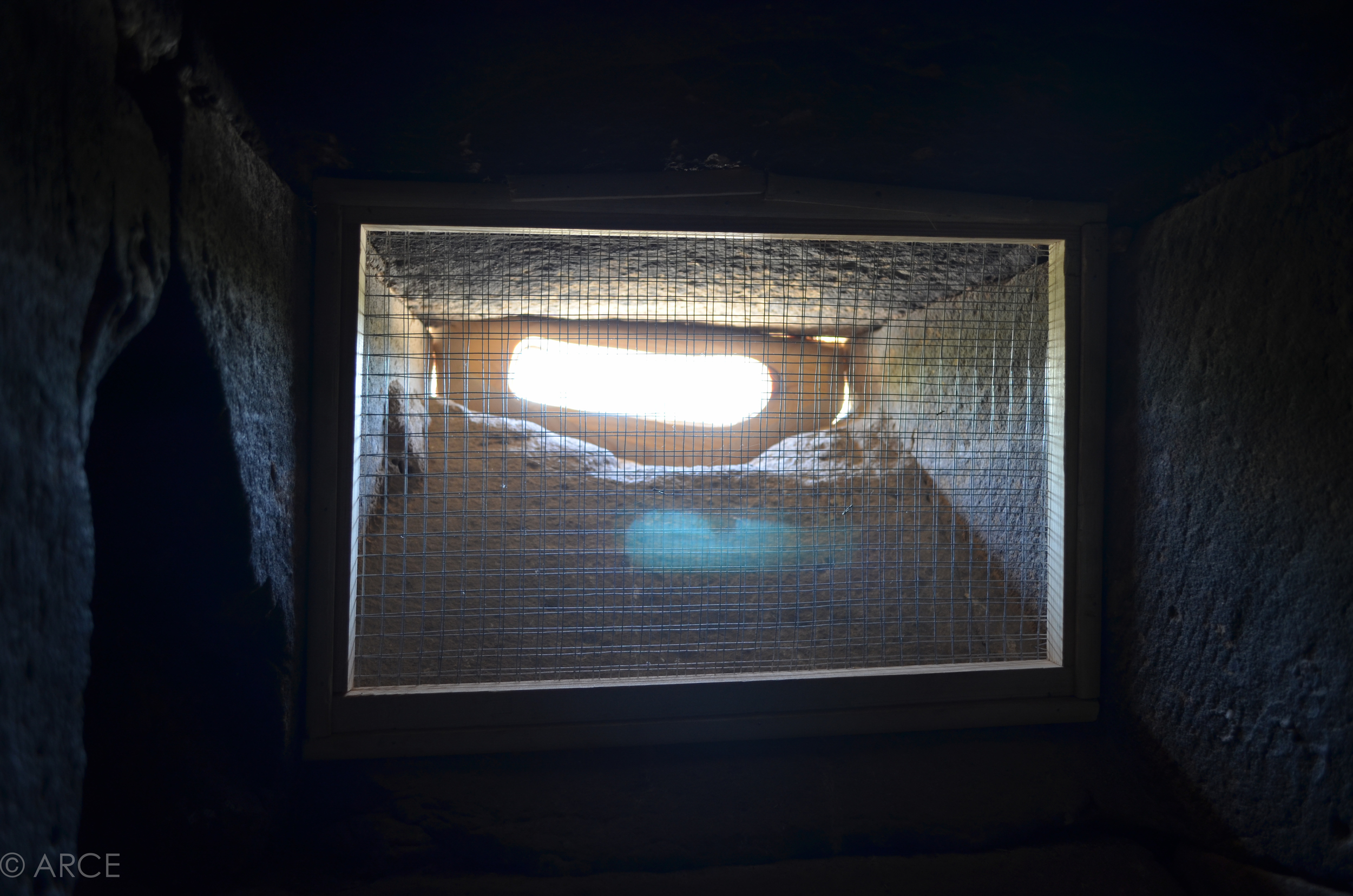

Bats roosting in one of the four side chambers in the temple. A small skylight in the ceiling was one of multiple egress points allowing the bats to enter and exit the temple. The skylight is shown both from inside looking up (left) and outside, looking down (right).

Image © ARCE, 2012

Dr Christian Dietz, a bat biologist in the Department of Animal Physiology at the University of Tübingen, identified the species as Asellia tridens.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Egyptian monuments are often streaked with bat and bird excreta. While historic sites are frequently sealed to prevent infestations, the closure systems are rarely made of durable materials and are poorly maintained.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Guano deposits proved the best indicator of roost locations and aided in estimating colony size between three to five hundred mature bats. No flightless young were observed.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Guano deposits were collected and tested in a Cairo laboratory for the presence of harmful fungal and bacterial growths, principally Histoplasma capsulatum.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Planning for sealing of the temple openings.

Image © ARCE, 2012

A team of local carpenters sealed the temple openings with wooden frames and a double layer of heavy duty, stainless steel screening with a mesh size of 1 cm2. The design was intended to minimally alter the original light levels and airflow within the temple. Taking into account the historic fabric, screens were fitted tightly in place without the use of screws, adhesives, or other invasive means.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Construction of screens on the temple's roof terrace.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Window openings on the temple's south facade, shown before (left) and after (right) closure with screens.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of window closures on the temple's south facade after completion. The wooden frames were painted to match the color of the surrounding stone.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of a window closure on the temple's south facade after completion. The frames were individually cut to precisely fit the contours of the original openings.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of a window closure on the temple's interior south wall after completion. A double screening system was implemented wherever possible to act as a backup.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Closure of temple openings with wood and mesh screening.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Closure of temple openings with wood and mesh screening.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Closure of temple openings with wood and mesh screening.

Image © ARCE, 2012

A bat shown exiting the temple through one of two major egress points just after sunset. The most successful means of eradicating a bat infestation is through exclusion, allowing the bats to exit the roost naturally for nighttime feeding and then sealing points of egress to prevent their re-entry. Exclusion must be repeated on a nightly basis until all individuals have departed.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Planning for repointing the exterior building fabric. Bats have the agility to crawl through very small openings including cracks. As a result, repointing was necessary.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Asellia tridens bat taking refuge in one of the many thin cracks running though the building fabric.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Preparation of lime mortar for repointing of the temple’s fabric. Fired bricks were crushed to provide a portion of filler for the mortar.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Preparation of lime mortar for repointing of the temple’s fabric. Brick dust and local sand were sieved and washed to provide filler for the mortar.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Multiple field tests were carried out to establish the ideal lime to fillers ratio for the mortar mix.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Repointing and filling of the temple’s exterior cracks with a tailor-made lime mortar.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Repointing and filling of the temple’s exterior cracks with a tailor-made lime mortar.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Repointing and filling of the temple’s exterior cracks with a tailor-made lime mortar.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Repointing and filling of the temple’s exterior cracks with a tailor-made lime mortar. The north facade is pictured before (left) and after (right) repointing.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of a large crack in the north facade before (left) and after (right) repointing.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of a large crack in the north facade before (left) and after (right) repointing.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of a large crack in the north facade before (left) and after (right) repointing.

Image © ARCE, 2012

The original plaster on the temple roof had largely weathered away, resulting in exposed joins and depressions where water could pool. Previous water infiltration had resulted in visible damage to the building interior. These joint were also filled with lime mortar.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Detail of roof joint after filling and repointing with lime mortar.

Image © ARCE, 2012

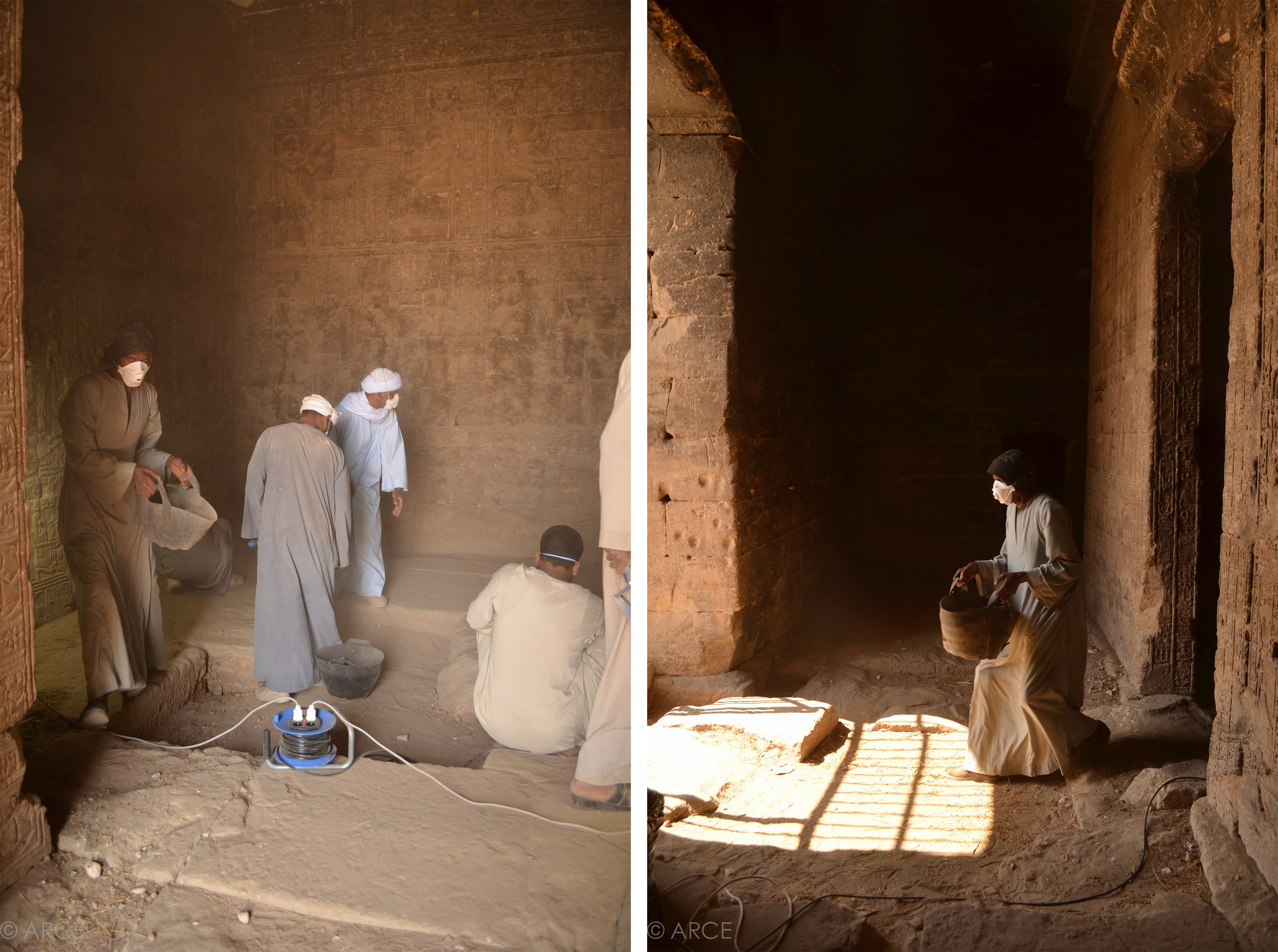

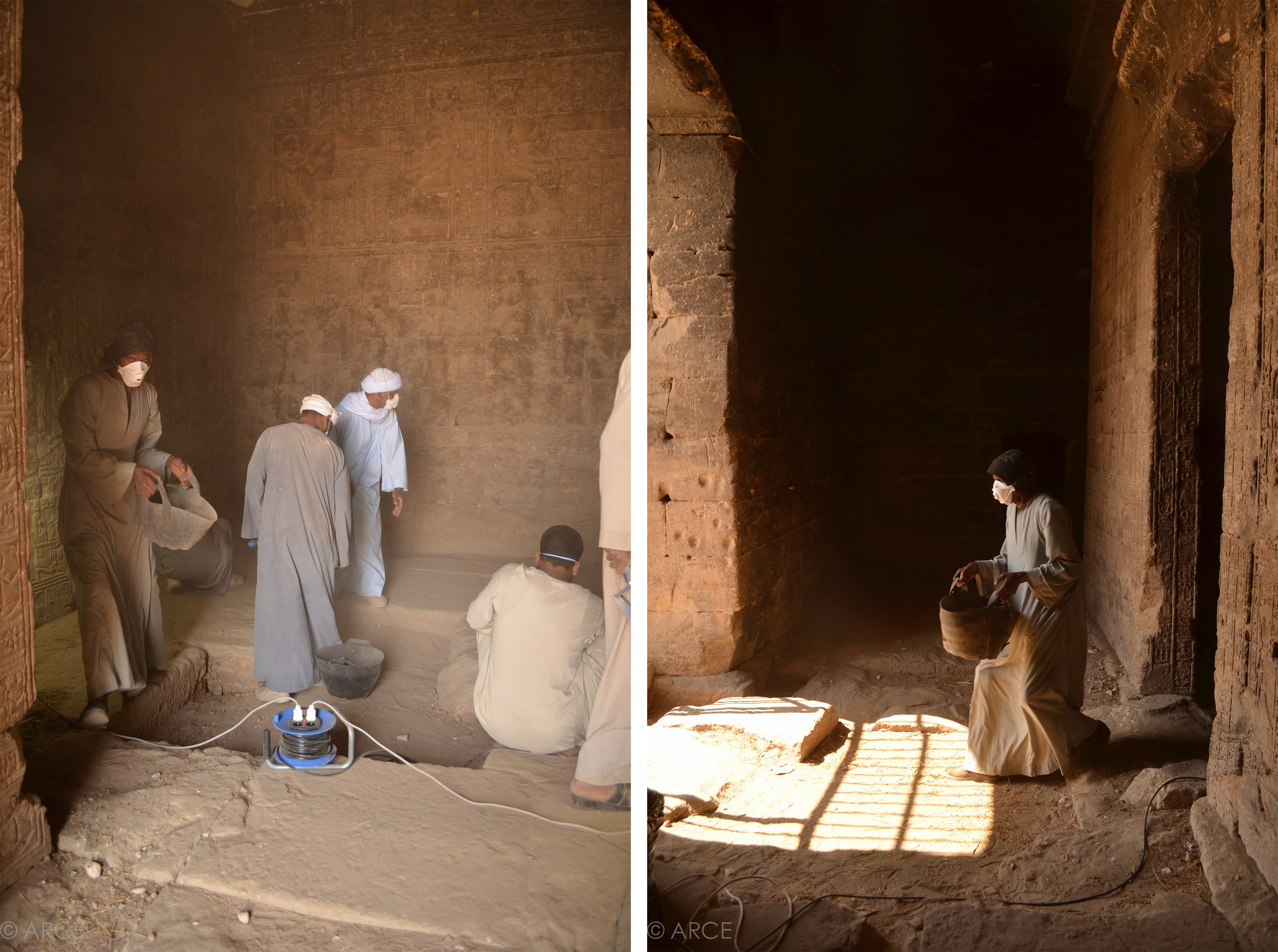

Once the bats had been permanently excluded, thick deposits of dust and guano were removed from the floors of the temple. All debris was reviewed for archaeological material before disposal.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Removal of thick dust and guano deposits from the floor of the temple. Dust movement was kept to a minimum by collection with trowels rather than brooms and was regular removal from the temple as it accumulated.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Following cleanup, preparations for work on the interior painted reliefs could begin. An initial step included the erection of a custom wooden scaffold, constructed by a team of local carpenters.

Image © ARCE, 2012

The custom-built wooden scaffold, providing access to the painted reliefs on the interior walls of the naos.

Image © ARCE, 2012

Upon the completion of preventive interventions, work was initiated within the naos, beginning with a condition survey and documentation of the painted reliefs.

Image © ARCE, 2012

A condition assessment within the naos demonstrated that the decorative relief was generally in stable condition. The limited time remaining in the work season was dedicated to cleaning trials.

Image © ARCE, 2012

The team.

Image © ARCE, 2012